The BBC adaptation of Sally Rooney’s bestselling novel tells a love story through fragments of memory. Connell and Marianne grow with each other, and so too do those watching. From Imogen Heap’s ‘Hide and Seek’ to Nerina Pallot’s cover of ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart,’ music acts as a pivotal trigger to orchestrate such memories – Caitlin Quinlan feels through her own relationship with teen dramas to piece it all back together.

‘Hide and Seek’ by Imogen Heap might be familiar to many people of my generation, either from a Saturday Night Live skit that parodied an episode of the hit US teen drama The O.C., or from that source material itself. In the show’s season two finale, troubled high school socialite Marissa Cooper shoots protagonist Ryan Atwood’s brother Trey in an attempt to stop a lethal fight, to the sound of Heap’s tender, sweeping tones. The parody mocks the melodrama of it all, but as a starry-eyed pre-teen, for me it was monumental.

The TV shows I loved dearly, like The O.C., extended themselves into 25-episode seasons, the minutiae of drama constructed week by week until catastrophe or death befell their characters. These were shows that entered me into a world of adolescent longing and angst, that let me live vicariously through their conventionally attractive characters who fell in and out of deeply important relationships in their sun kissed mansions. I yearned for a love story of my own, for a heart-crushing romance that would engulf my entire world just like theirs did. I can still remember the songs that soundtracked other key plot moments too, the first kisses or the funerals. These on-the-nose sad acoustic cues were structurally integral, and did much of the emotional heavy-lifting. Still, they got me every time.

So to hear ‘Hide and Seek’ used pointedly again in a new drama many years later, this time in the TV adaptation of Sally Rooney’s acclaimed novel Normal People, felt sublimely targeted. Whether intentional or not, it was a gateway into the world of protagonists Connell and Marianne that I wasn’t expecting. I had liked the book, found Rooney’s writing to be remarkably unremarkable in a clever, knowing way. I felt she understood our generation and I appreciated the gravity with which she told our stories. This dramatisation took on a different tone, however, with that needle drop. I understood the space I was being sent back to: a space of lonely youth and uncertainty over your own worth – the space Marianne occupies for much of Normal People. The song reminded me of a time and a person I’ve now grown out of, and in doing so exposed a formula for examining how the show would continue to evoke memory and the ache of time gone by.

The characters in The O.C. were far from normal people, and Connell and Marianne might be too in their exceeding intellect and traditional beauty, but their stories grasped my emotional attention. Where Normal People succeeds on screen is in its commitment to Rooney’s text – but its acknowledgement of such predecessors was a special, idiosyncratic detail that felt attuned to me all these years on, making it a poignant extension of my beloved teen drama collection. I absorbed each episode through an older mindset, as someone who has now experienced and, hopefully, learnt from the turmoil of young romance. The show began to unravel the threads of past feelings within me, engaging with a space of memory, or a memory logic, in its narrative that invited a new maturity in my thoughts about my own growth.

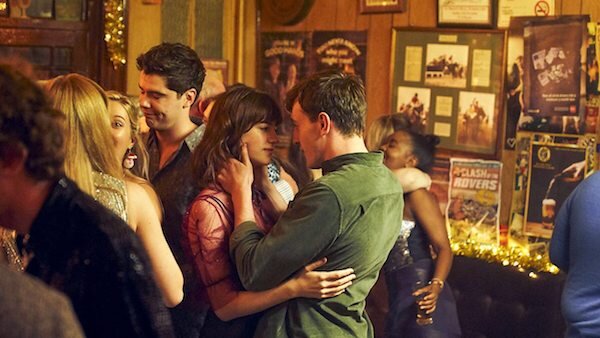

Delving into this memory-scape, directors Lenny Abrahamson and Hettie Macdonald are shrewdly considerate of Rooney’s structure of time in the novel, flitting back and forth between present and past. Adopting the non-linear style, the directors coax out the interiority of Rooney’s prose through jumps and fragments of Connell and Marianne’s lives, which come to feel more like memories pieced together from afar than experiences in the moment. We watch the cycle of life for these characters, stumbling over words and feelings until they’ve hurt the other beyond repair – or so it seems until they fall into bed again and the intensity of their physical connection wipes the slate clean. With every reconnection, Marianne closes her eyes and breathes Connell in as if he’s the only oxygen left in the atmosphere. He kisses her hungrily, but every so often presses his lips softly to the spot where her shoulder meets her neck. They repeat “It’s not like this with other people” to each other, again and again. If the pace and magnitude of their affections – the way they engulf one another – seems far fetched, it is because these snapshots take on that effect of memory, of fleeting images and pains embedded in the consciousness they seem to share. We are not here to witness time merely elapsing. We are with them in the essence of the moment, in the kitchen after a fight, in an art gallery after an inopportune kiss, on the edge of a swimming pool with a hand around a waist.

If Abrahamson in his half of the series ushers in this effect with a familiar approach of dreamy close-ups and breathless montages, then Macdonald pushes it to its best later on through an intriguing restructuring of time. In episode 6, Abrahamson’s last episode, we open at a close. A glass smashes in a sink, and a crying Marianne turns from the darkened window before we cut back in time, and she’s stood in the same position on a sunny morning with Connell approaching to kiss her. The episode is a miniature of the series as a whole – we gaze upon their moment of happiness having already witnessed the sadness that inevitably follows, an inherent sadness that pervades their relationship from the beginning.

Abrahamson is keen to mirror the pair whilst apart, demonstrating a shared memory or consciousness. They eat dinner at the same time in their separate family homes in one moment, walking with their backs to us across green spaces in another. Even the movement of a secondary character like Marianne’s brother, who leaves her in the kitchen to then be seen in a pub with Connell, builds on this connection. Macdonald adds her own spin on this technique with an identical shot in episodes seven and 11, of Marianne lying on a sun lounger in her front garden. This jolt in the timeline, a sudden “Where are we?” moment, reinforces the discerning power of memory in the story’s code. Marianne’s life at home is defined by repetition and loneliness – the identical shots evidence that. When she is in Carricklea, without Connell, nothing changes.

The vibrancy and definition of Marianne’s life appears in other moments, other places. It is found whenever her and Connell have their “mutual, equally involved” sex, as she puts it, the seconds before a kiss they both know they’re longing for, or simply cycling together down a lane in the Italian countryside during a more carefree moment. Darker scenes are also defined in their lives, as time sputters and spins forward through trauma; when Connell is lost in the grips of a panic attack, or when Marianne leaves a situation of pain she felt she deserved, where the fragmentary editing reveals her escape before it documents the suffering – in a reverse effect to episode six.

Throughout the series, songs such as Yazoo’s ‘Only You’ or a Nerina Pallot cover of ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ play over the credits, brazenly embracing a lack of subtlety for the sake of heartfelt reminiscence. The years have not yet hardened me to this obtuse technique. These songs act as poignant triggers of memory as sensitive, often melodramatic, carriers of deeply felt sentiment. Heavyweight teen dramas gave me a need to attach meaning to every note. Normal People grasps this tendency and embeds it within its framework, giving weight to the salient touches that draw us back to the past. Whereas the structural experimentation with time denotes transient, evasive memory, the use of music adds a grounded certainty to the emotions expressed. Tender clarity intertwines with hazy recollection here, an evocative portrayal of how memory can function.

Normal People is the story of these fragments of a relationship pieced back together. The act of looking back from the very beginning implies its evanescence, its transitory joys and pains. In some ways this is a relief, to recall time knowing it has now passed, but floating in the memories of others encourages your own lingering contemplations on what life was like then. I felt situated within my own memory when hearing ‘Hide and Seek’ and was able to register the distance between then and now, inviting reflections from a position of maturity. For others, a pertinent line of anguish-laden dialogue or the sweaty sight of a Gaelic football shirt might do the trick. These sparks are enough to unwind years. At this age, perhaps more jaded and less ingenuous, I find myself no longer looking for the vicarious escape of imagining a life ahead of me. Instead I take the time to remember what came before, to feel a few bruises of the past, and to appreciate an invaluable time of growth.

Caitlin Quinlan (@csaquinlan) is a film writer and Bechdel Test Fest team member from London. She regularly contributes to Little White Lies, Sight & Sound, and The Skinny.