What’s more terrifying than losing track of yourself? In body-horror Cam, the female sense of self is used as one woman’s greatest woman, as one cam girl grapples with her internet persona and the dangers of a life lived online. Gemma Mushington explores the dangerous dynamics of the Netflix film and celebrates the subversion of the Final Girl.

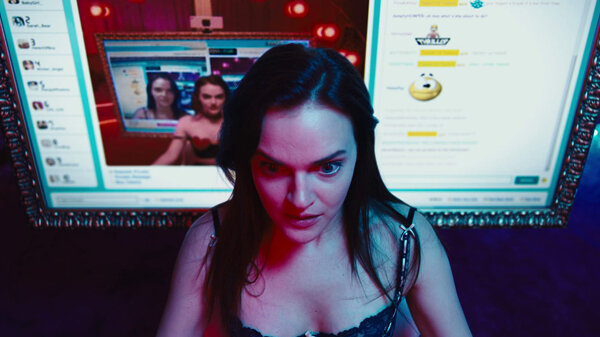

Neon-lit horror film Cam takes a stab at exploring the complex issue of internet identity and autonomy within the landscape of online sex work. Opening from the perspective of an adult cam site viewer, we look into Alice’s (Madeline Brewer) baby pink-drenched room through the slightly grainy lens of her webcam. She dives into the scene in just knickers, socks and a varsity jacket. She’s dressed like a lads mag girl-next-door pin-up, but with the face of an actual girl-next-door – pretty, but not intimidatingly so. Streaming live, she jokes and teases, talks to the members like they’re her friends. It’s not until two minutes and forty seconds in that we cut to being in the room with her, the webcam and chat feed looming over us. She’s unashamedly sexual, but lets you take the lead; perky and bubbly, but mature enough in age. She laughs at your jokes, and any push back is playful banter. Instantly, we like her.

Asking viewers to vote on what sex toy she uses today, Alice – or, her cam persona Lola – is sweet in her ironic innocence, but never childish, which makes her appealing. She’ll dance around her room with a giant stuffed teddy bear, but she does not feign unintelligence or use a childlike voice. This presentation is unthreatening to masculinity: she’s submissive, and sustains the girlfriend experience. An anonymous user asks her to use a knife. He eggs her on. She bans him, but he returns wanting her to “cut [her] pussy open,” and the other watchers either defend her or encourage it – all this commotion brings only more viewers and tips into her room, her ranking rising to the Top 60 Girls board, a list of the most popular cam models on the website, which Alice obsesses over throughout the film.

She can’t take it anymore, she pulls a blade out of her box of sex toys, shouting “Is this what you want?!” and proceeds to slice her throat open, blood spilling down her chest. We watch from the view of the webcam, her head hangs in what would be silence – if it weren’t for the stream of tips coming through, as well as comments, GIFs and hastily-made memes. Back in the room with her, we pull in, she lifts her head, revealing that it was simply a stunt for the show, ripping the latex wound from her neck with. “Gotcha.”

Watching Alice silent, covered in blood, for a moment we are reminded of the opening sequence of Wes Craven’s 1996 Scream. After 12 minutes of psychological torture and running up and down stairs, flirty and fun Casey (Drew Barrymore) is slaughtered and we move on to the pretty, yet unassuming virgin Sidney (Neve Campbell) – the true protagonist of the film. But Alice survives, despite her profession as a sex worker, bringing a new perspective to the Final Girl. This horror film trope was coined by Carol J. Clover in her book Men, Women and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. The Final Girl is virginal, modest, intelligent and the one who survives until the very end – think Sally (Marilyn Burns) in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, who cares for her paraplegic brother and is otherwise lacking in personality other than being a teenager, or Laurie (Jamie Lee Curtis) in Halloween, who’s also a typical teenage girl and the local babysitter. Alice, or at least her cam identity Lola, does not embody the Final Girl in the traditional sense. The film challenges this view of the female horror protagonist and what it means to be in her body – Alice is not punished for her overt display of sexuality, and is not dispatched in favour of a more traditional female protagonist. She is career-driven, logical, and cares about her family. There is more to her character than just being an expendable body.

The film’s screenwriter is author and former camgirl Isa Mazzei, who knows first-hand the ups and downs of camming, and discussed her irritation at the mainstream media’s poor representation of sex workers – as displayed in countless episodes of crime shows such as CSI and Law and Order, but also comedies like Family Guy, Arrested Development and The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. They’re treated as dumb, disposable and harbouring some long-standing daddy issues, two-dimensional props that make for good punchlines or an easy death. It’s not that Alice is a rare exception when it comes to sex workers – she’s not better than any other sex worker, she just is a sex worker, who also happens to be a real human being. What a twist.

Now two separate entities, Alice watches from her own camming room as Lola streams live an 80s aerobics themed show from a replica room. At this point, Alice has been stalked by Arnold, a dedicated member known by his online handle Tinkerboy; publicly outed to her family at her brother’s birthday party by one of his friends; is losing earnings and success; and has had her own camming rules broken, such as never faking an orgasm. While Lola giggles and enjoys herself, a hunched over, nail-biting Alice watches disturbed and frustrated, as she climbs to the Top 30 Girls list. Alice logs in as a member under the name MrTeapot, tipping Lola to hit herself, harder and harder. Happily, Lola complies and Alice seethes watching Lola excel.

From behind the fluttering of a feather fan, Lola reveals a gun. Alice’s room dims, soon she’s lit only by the computer screens, as panic sets in. Lola playfully asks for tips – to lick it, to suck it, to load it and, eventually “How about 100,000 for me to make it explode?” The members don’t hesitate to help her reach her goal. She shoots herself through the mouth, blood splattering behind her, she drops back, dead. Instantly, Alice falls into a panic attack having just witnessed her own death. But, with the chime of the tips coming in and her ranking climbing, Lola gets up, perfectly fine, and overjoyed at making it into the Top 20. Lola is immortal, all powerful, elusive and, importantly, lacking in a soul. Lola is just a body, there is no ego to damage, lasting trauma, or fear. Alice fails to contend with Lola because she is inherently human, but if horror films have taught us anything, this will be what saves her in the end.

If Alice is our human, is Lola this film’s monster? The Final Girl trope shares similarities with the philosophy of monster movies. If Godzilla is a representation of the Japanese population’s fear of nuclear weapons and the werewolf is a symbol of man’s repressed primitive urges, what is Lola? In their essay, Embodied Identity in Werewolf Films of the 1980s, Dutch scholars Koetsier and Forceville use the metaphor “the deviant identity is the transformed body,” to verbalise the concept behind werewolf films. The “deviant identity” tends to be a social fear or taboo. Alice is the Final Girl, as opposed to the “deservingly” killed-off slasher victim, and Lola is not a personification of the demonisation of sex or social media, but she is a symbol for the selfish and dangerous power of man when in possession of the privileges granted by having an internet identity. Alice’s body and brand are stolen and used for the financial gain of some anonymous user, who now receives Alice/Lola’s income from the cam site. The user is taking advantage of their own lack of identity and the abundance of Alice’s image on the internet. Cam questions what level of ownership we have when any identity is public – where we end and the persona begins. Lola’s position as a body protects whoever is standing behind it, because she lacks a human identity, but attracts with her internet identity.

What makes existing on the internet even more frightening, for Alice or any camgirl living a double life, is that you will always be seen as your online persona. Lola is Alice’s creation; while Alice is anxious and introverted, Lola is bubbly and carefree. But they have the same face, the same bank account and the same reputation. When her cam site account gets stolen, Alice’s image and livelihood are in the hands of someone or something else. Essentially, both identities are stolen in the real world and the online world. Cam quickly moves away from the tired and offensive “disposable sex worker” trope perpetuated by the entertainment industry, from Law & Order to Family Guy, in favour of a story and character with more substance. Mazzei and Goldhaber show us just how horrifying the power of identity and anonymity are without putting just another dead sex worker on our screens.

Gemma Mushington (@gemma_ym) is a London screenwriter, blogger and journal keeper. You can catch her rambling about film on Letterboxd, wellness on her blog UnUnhealthy and the unfortunate fortune of being alive on Medium. She is an appreciator of comfy socks, scented candles and clever card tricks.