Bret Easton Ellis’ novel American Psycho is a wry autopsy of male vanity, that often comes at the expense of women. Katie Goh dissects how filmmakers Mary Harron and Guinevere Turner’s adaptation manages not only to dismantle the male gaze, but entirely reassemble the story with a female one.

My first encounter with Patrick Bateman was in American Psycho, the novel. I was 15, finished with Stephen King’s bibliography and looking for a new monster. What I wasn’t expecting was to find a novel that loved its monster as much as this man loved himself.

American Psycho has a simple plot. Its protagonist Patrick Bateman (played by Christian Bale in the 2000 film adaptation), is a self-obsessed Manhattan “yuppie” by day, and self-delusion serial killer by night. Set during the Wall Street boom of the 1980s, Bateman’s world is a swirling void of shiny consumerism, existential desolation and cocaine-fuelled absurdity. He has a fiancée, Evelyn, who he has no feelings for, a job he hasn’t had to work for (daddy owns the firm) and the world at his feet. But even with all this, Bateman still isn’t fulfilled. So, he takes to serial killing, targeting mostly sex workers and homeless people. Patrick Bateman is a sociopath and a shark: he feels nothing and he can’t stop. He’s a symbol of modern American consumption, addicted to his appetite and yet unsatisfied, everything author Bret Easton Ellis despised, yet saw in himself and the rest of the country’s young men.

Before I’d made it half way through the novel, I tossed my paperback copy across the room. I think it was the description of a rat gnawing on a woman’s vagina that was the last straw. There were so many descriptions of women being raped, tortured, murdered, dismembered and occasionally eaten in those pages that my initial feelings of horrified fascination had turned to repulsion, and then into boredom.

My second encounter with Patrick Bateman was in American Psycho, the movie. Slightly older and much more sceptical for a reunion with the serial killer, I expected the movie to be a bloody, porny slasher version of the book. So imagine my surprise when what I discovered was an adaptation that somehow got what the novel was trying to do, more than the novel itself. I remember thinking, “Did they make American Psycho… feminist?”

Director Mary Harron and co-writer (as well as actor) Guinevere Turner went into American Psycho knives out. Referencing the infamous rat eating moment from the novel, Turner told Dazed, "I remember reading that and thinking, ‘Fuck you Bret Ellis, that’s never gonna get out of my vision!'” Harron and Turner admired the novel’s biting critique of 1980s America and slippery portrayal of male vanity, but wanted to pull out more of the satire and leave the pornographic violence behind.

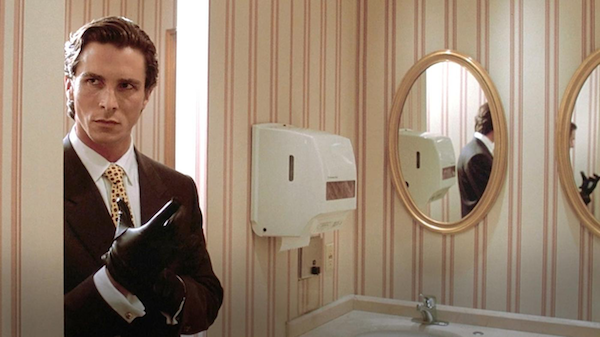

Both film and book follow a similar plot, but what makes them feel so strikingly different is how we see the events unfold – the gaze of the narrator versus the gaze of the camera. The best example of this is American Psycho’s representation of sex and violence. Shedding the detailed gratuitous brutality of Ellis’ novel, Harron and Turner are more interested in what happens around Bateman’s attacks than the acts of violence themselves. Large portions of time are dedicated to Bateman’s pre-murder rituals – choosing a song, hand-washing, buttoning up a raincoat, a quick moonwalk – but most of the violence happens off-camera.

The difference in how the novel represents violence versus the film is often said to come down to a male gaze versus the female gaze. We talk so much about gendered gazes, particularly the female gaze, that it has become a buzzword, often applied lazily and reductively to any movie directed by a woman. Let’s get one thing straight: Harron’s gender isn’t the sole reason why American Psycho has a female gaze, although, I imagine it helped.

In her famous essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, Laura Mulvey was one of the first writers to define the terms ‘male gaze’ and ‘female gaze’ in relation to cinema. “In a world ordered by sexual imbalance,” she wrote, “pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female.” The heterosexual male gaze is therefore the normative gaze, one that helps to reinforce a world ordered by sexual imbalance. Think Megan Fox leaning over a car hood in Transformers, Hitchcock’s camera panning up Grace Kelly’s body, even old school Disney princesses – all are subjected to the male gaze and objectified under it.

The female gaze feels a little trickier to define (likely because it’s not the normative gaze). It’s not as simple as panning a camera up and down Channing Tatum’s body because objectifying a male body doesn’t undo the male gaze, the manifestation of unequal cultural and social power. Instead, the female gaze picks apart that power. It can be seen in how Jennifer Kent subverts the common gratuitous gaze of rape scenes, by letting us see the events through the eyes of her protagonist in The Nightingale. Or it can be seen in the unapologetic assertion of Black lesbian cinema in Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman. The female gaze is built into the structures of these films, consciously rejecting the male gaze which is just there in cinema, a result of decades of men making, critiquing and canonising films. The female gaze is uncomfortable because it’s not what we expect. It’s not palatable. We have to learn the female gaze in the same way we have to pick apart the male gaze.

There’s a scene in American Psycho which I think perfectly sums up its female gaze. Bateman is having sex with two women, a scene that could so easily become pulpy porn. But Harron chooses to linger the camera on Bateman’s body rather than the women’s. He flexes in the mirror, more interested in seeing how he looks while having sex than engaging in it. The female gaze is the details, like the looks of boredom on the women’s faces while Bateman recites a terrible music review, and it’s a gaze that the audience and filmmaker see, but not Bateman. These details are subtle but essential, letting us in on the women’s perspectives as they feign interest before faking an orgasm.

The female gaze is there throughout the film. It’s there when Bateman tells a bartender she’s “an ugly bitch” behind her back. She can’t see him but we can, and we see all of Bateman’s cowardly violence: screaming at an elderly Asian woman in a laundromat; his sweaty fury over business cards; his two-faced panic in front of a police detective. Harron continually places the viewer outside Bateman’s subjectivity so that we see how he looks to those around him – pathetic.

Ellis made Bateman a monster, Harron and Turner turned him into a joke. But that doesn’t mean they don’t understand the violence and devastation that Bateman, and men like him, leave around them; like a toddler having a tantrum, they’re just not interested in humouring it. In Bateman’s world, he is the consumer and everyone and everything around him is his spectacle. In Harron’s world, Bateman becomes the spectacle.

In a 2010 interview with Movieline, Ellis gave his own take on cinema and gazes. “There’s something about the medium of film itself that I think requires the male gaze… it’s a medium that really is built for the male gaze and for a male sensibility. I mean, the best art is made under not an indifference to, but a neutrality [toward] the kind of emotionalism that I think can be a trap for women directors.”

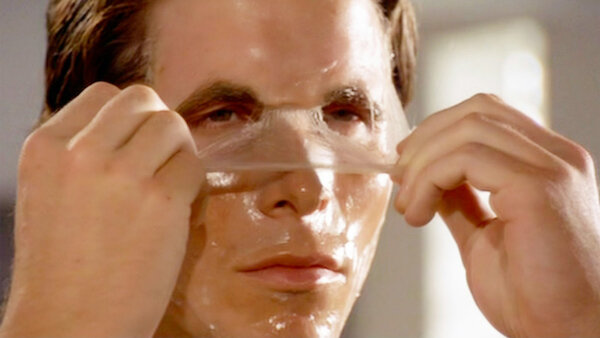

Ellis is missing (or perhaps rejecting) the irony that a female gaze is what it took to transform a novel that paints a portrait of a man’s pain on a foundation of misogyny, into one of cinema’s best critiques of masculinity under the patriarchy. Harron’s American Psycho peels off a mask of privilege, greed and charisma to expose Bateman’s world, our world – a world in which women are as attainable, consumable and disposable as the latest car model or designer suit – as an empty, tired con.

Katie Goh (@johnnys_panic) is a freelance arts writer and editor based in Edinburgh. Her words have popped up in The Guardian, Sight and Sound, Dazed, The Independent, The Skinny, Huck, and more.