The erotics at the heart of Jane Campion’s new film The Power of the Dog, her first feature about a man, hone in on material details: a stiff rope, a smooth leather saddle. There’s repression and lust in the dance between love and death – Anahit Behrooz dives deep into this world’s breathtaking detail.

Jane Campion – cinema’s famed chronicler of women – knows men. She knows their insecurities and their swagger, their tenderness and their ragged edges, their unpredictable ferocity and their oh-so-predictable tendency toward domination. When The Power of the Dog – Campion’s first film in 12 years – was announced, much was made of the New Zealand director’s decision to feature a male protagonist for the first time.

Yet Campion’s distinctly female-oriented filmography has always, in some ways, also been about men. From harrowing and Palme d’Or-winning period piece The Piano to much maligned erotic thriller In the Cut, Campion’s films examine with grim, relentless determination the bloody reality of what it means to desire and pursue and fuck and be fucked by men, of what happens when the violence of masculinity – its brutality and precarity and insidious, capillary nature – meets the vulnerability of yearning and intimacy. How can desire operate, Campion’s films ask, in a world where it is so bound up with threat?

Campion’s protagonists teeter on the edge of sexual obliteration because they have no other choice – and so it is with The Power of the Dog’s Phil Burbank, played with nervy menace by Benedict Cumberbatch in a study of grimy, explosive queer repression. Enacting a cruelty all the more terrorising for its absurdly childish nature, Phil – sweat-smeared and dust-caked – goadingly calls his brother George (Jesse Plemons) “Fatso”, torments George’s new wife Rose (Kirsten Dunst) with petty whistling and cutting remarks, and bullies her teenage son Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee) for his gentle nature. His performance of brutish, domineering masculinity is almost ridiculous in its uncompromising nature; striding around his and George’s ranch with an exaggeratedly bow-legged gait, Phil refuses to wash and castrates wild-eyed bulls with his bare hands, performing the role of cowboy with overly keen ease.

Yet as is the case across Campion’s oeuvre, Phil’s sexual desires are a soft underbelly whose open viscerality is belied by their intense suppression. The shadowy figure of Bronco Henry, a long dead cowboy who reared Phil in the ways of riding (in every kind of way) looms over his life decades on, occupying a liminal position between myth and man, abstract memory and stifled sexual longing.

Desire in The Power of the Dog is so latent, so ambivalent, that when I first saw the film at this year’s Venice Film Festival, it barely registered: I recognised Phil’s queer repression and the charged struggle for power between himself and Peter, yet it took weeks for Campion’s heady exploration of violent lust to seep in so utterly that I felt gritty with it. The Power of the Dog’s, well, power is in how its profoundly erotic charge takes over, and indeed thrives off, the gaps between people: in what is unsaid and denied and deflected, so that both desire and cruelty are given air and soil to grow.

The looks and touches and glances between Phil and Peter make up the usual grammar of longing buried beneath masculine bravado as their relationship veers from fractious antagonism to something more tender – or twisted. But erotic expression in The Power of the Dog is really an explicitly material one, communicated through a series of totem-like objects containing and conducting queer desire and its concomitant violence in the harsh rural circles of 1920s Montana.

Varying forms of male closeness may be normalised in this world – ranchers swim and lounge around naked in the watering hole, they dance together and sleep in the same rooms – yet these nude male bodies and homosociality shore up the toxic masculinity of their social order. With objects, however, Campion focalises the transgressive nature of desire beyond these accepted bonds. It is in touch – its tenderness, materiality, and irrevocable undeniablity – that queer desire finds both expression and undoing.

In his theorisation of eroticism, French philosopher Georges Bataille writes: “Eroticism, it may be said, is assenting to life up to the point of death”. Nowhere is this entanglement between sex and death made more explicit than in the constant, gleaming presence of leather in The Power of the Dog. A saddle previously owned by Bronco Henry sits in pride of place below a grave plaque, while a stiff rope braided from strips of cowhide becomes the catalyst for Phil and Peter’s standoff.

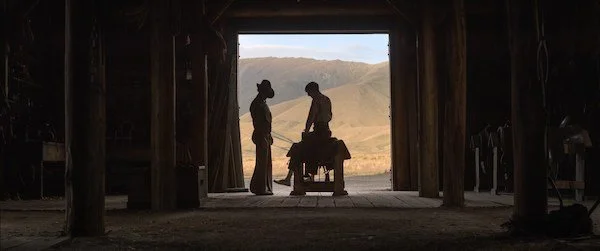

Set on a cattle ranch, Campion’s film leans into the life cycle of these wryly kinky objects so that the erotic potential of leather becomes a living, breathing thing. A swarm of cattle ripple like water through the wind-chapped hills, lowing and butting heads, before being mercilessly strung up and skinned.

The saddle is one of few mementos from Phil and Bronco Henry’s savagely loaded relationship, and his encounters with it – for they are encounters – are steeped in brazen, shaking desire. When, in one of Campion’s wickedly sly touches, Phil overhears his brother having sex with his new wife, he goes to the saddle for his own carnal tryst, his hands pressing firmly over its curves and horn, the leather creaking beneath his searching fingers – an affair of marked and stunted sensuality.

Later, Phil crafts another leather-bound memento to give to his own charge (Campion takes care to stress that Peter is the age Phil was when Bronco Henry and he would ride together). Throughout The Power of the Dog, rope as object is bound up with threatening connotations: Peter’s father was found hanged by his son, and the rope Phil is braiding conceals its own secrets, braided not with love, perhaps, but with a bewildered, brutal desire that can barely acknowledge itself.

Strands of cowhide are knotted tight with tension, the length of the rope pulled taut against Phil’s leather-clad, bracing hip bone. Yet Phil’s desire for Peter, for Bronco Henry, for viscerally uninhibited sexuality (“You want me, Mr Burbank?” Peter asks blandly, kneeling before him) is too little, too late, inextricable from the savagery that has corrupted the rest of the embittered rancher’s life: the hundred vicious cuts delivered to Rose, the brutality with which Phil reacts to perceived weakness. Both Phil’s vulnerability and violence are monsters of his own creation, and the effects when the two collide are calamitous.

BDSM implications of leather aside, deceptively softer items are just as dense with suppressed desire. The flowers Peter crafts as dinner table dressings, from strips of paper cut like hide, are violated by Phil. His finger pushes deep into their centre before setting them alight: a quashing not just of Peter’s perceived effeminacy but Phil’s own anally-oriented desires. Later, Phil takes out another memento from Bronco Henry, a handkerchief he trails lightly, tremulously, down his own stripped body as soft, glowing sunlight streams over him.

It is striking that, in the same moment, Peter discovers Bronco Henry’s stash of pornographic magazines mere feet away, striking that Phil hadn’t used them to more expediently get himself off. Clearly, the handkerchief is not about expedience, or pure sexual release. The sweat and dust and memories of Bronco Henry that permeate the handkerchief are what make it both erotic and transgressive: an entire narrative of desire and denial contained in its folds.

And then there is the cigarette shared by Peter and Phil towards the end of the film, the star of 2021’s unquestionably horniest scene. The two are in the barn late at night, Phil finishing Peter’s rope with fatal determination. Phil’s tobacco, loosely thrown and caught in a gesture of performed ease and camaraderie (what is it, incidentally, about men capably throwing and catching things that remains so shudderingly erotic?), is being rolled by Peter. They are discussing Bronco Henry, how profound his and Phil’s bond was, how he once saved Phil’s life by sharing body warmth with him in a blizzard. “Naked?” Peter asks, his gaze unflinching. Phil laughs shakingly.

Peter’s plans to destabilise Phil have long been in the works, are even now infecting Phil’s body, but it is here that the shift in power fully materialises: Phil’s careful confessional of his queer experience, and Peter’s incisive laying bare of it. And when Peter holds out the lit cigarette for Phil to inhale from between Peter’s fingers, there is a tentative longing to Phil’s plaintive gaze, a shy, almost virginal glance of barely contained wanting. Campion’s camera never unites them in frame: it is Peter’s fingertips, Phil’s flickering, lowered eyelids, Peter’s lips encircling the cigarette moments after Phil’s that piece together the intercourse at play. Campion’s masterstroke here is in delay, in a pulling away from consummation: a sexual intimacy fundamentally formed by the exercise of power over defenceless desire.

The vulnerability of sex, particularly when tied to masculinity, is a thread that runs throughout Campion’s work: it is when Phil drops his carefully maintained bluster in search of intimacy that he exposes himself to a well he himself has poisoned. Throughout The Power of the Dog, Phil and Peter circle each other, straddling proxies of their rival’s body and pulling bindings tight against their thighs.

Do they really desire each other, or is it all merely a power play? In this patriarchal and heteronormative reality, where desiring men always places the desirer in a vulnerable position, is there even a difference? Sex and its requisite yearning may well be about who you would gladly let inside you, who you would willingly trust with the rawest, most delicate parts of yourself. But they are also, as Campion’s cinema knows, and as Phil finds out, about who you might let destroy you instead. Who you might let – with surgical precision – flay you open, limbs pinned against a dissection table, before burying you deep beneath the freshly turned earth.

Anahit Behrooz is an arts journalist based in Edinburgh. She currently works as events editor at The Skinny, with words in Little White Lies, The Quietus, MAP Magazine, Girls on Tops and others. She likes beautiful films about women, old bookshops, and Dan Levy’s eyebrows.

Shop our special TPOTD edition Jane Campion t-shirt here.