As the 2020 film festival circuit adapted to a homebound, virtual environment, a number of titles addressed themes of female trauma and the subsequent ways we process it. But the medium, too, raised questions about the content warnings that prepare us for such sensitive material. Exploring photographic metaphors and the way we come to live with our grief, Lillian Crawford dissects the sensitivities of Pieces of A Woman, Still Processing and Promising Young Woman through a personal lens.

I attended my first international film festival in Spain last year, alone. Having just graduated, this was a huge step: until recently, depression and social anxiety had meant that I scarcely left my university room except to go to my safe space — the cinema. Watching four film premieres a day was wonderful, until I was watching a man forcing himself on a young woman in a film which had no content warnings in the press schedule. The past rose up in front of me and I lost myself. The cinema didn’t feel so safe anymore.

When we witness trauma on screen, it’s often used to push forward the narrative. Be it Alex DeLarge and his Droogs raping women in an abandoned theatre in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange or the unflinching ten-minute sexual assault in Gaspar Noé’s Irreversible, the camera shoots, and, having shot, moves on. It’s a narrative device, a short, sharp shock that deliberately leaves an unprocessed impression on an audience that lingers in the mind after they’ve left the film behind.

Beyond the largely exploitative rape-revenge genre, there’s an underwhelming number of films that sensitively approach the subject of female trauma. As over 50 percent of women experience trauma in their lives, for 10 percent of whom this will manifest as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), it’s a subject cinema should represent as a means of providing women with the language they need to describe their experience. Since PTSD was first assessed in relation to male Vietnam War veterans in 1980, it’s not surprising that many people still associate trauma with military conflict – but it’s a condition women are approximately twice as likely to develop than men.

As a woman with Complex PTSD, meaning that I’ve experienced multiple traumas over an extended period of time, it’s not as simple as avoiding every film rated 15 or 18. Some films I cannot watch, like A Clockwork Orange and Irreversible, without dissociating and experiencing flashbacks. That’s not because I haven’t processed my trauma – to a large extent, through therapy and medication, I have – but because those films don’t depict the processing of trauma in their narrative. We watch men rape women without witnessing the effects of those assaults on the female characters. We see them only as victims, when we need to see them as survivors.

When COVID-19 sent us all into lockdown in March 2020, I decided to use the time to focus on improving my mental health. For the first time in years I feel in control of my memories, to recall them on my own terms rather than being triggered by external events and appearing as invasive flashbacks. I’ve wanted to write about my trauma in a way that makes me comfortable, and I’m realising that this can often be achieved through recognising my experiences being represented in films.

Having been forced to move online by the pandemic, last year’s autumn film festivals were more accessible than ever – but I was struck by the lack of content warnings across the online platforms hosting the releases. A film such as Joyce Chopra’s Smooth Talk, which screened in the New York Film Festival’s ‘Revivals’ strand, has been available since 1985 and yet there were no descriptors of the harassment Laura Dern’s protagonist experiences for much of the final act. Films both have potential to aid the processing of trauma, and to reignite it. If we are to increase access to film criticism, safeguards need to be in place.

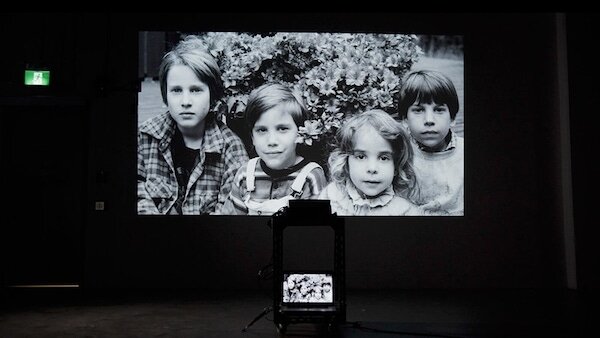

Nonetheless, a significant number of films about trauma directed by women were screened – many that are exceptional. One of the most extraordinary is a short documentary directed by Sophy Romvari called Still Processing, which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. While a large number of trauma cases are caused by physical abuse, Romvari’s film sheds light on the suffering people experience when they lose a loved one, or in this case, her two brothers.

Putting trauma into art provides means of externalising events, so they become something tangible that the artist can control, as opposed to a singularly internal experience. By sharing Still Processing with others, Romvari is sharing her trauma, and creating distance while simultaneously bringing her memories closer. “The scene where we look at home video footage, you can see both of us really struggle with memory, which was captured organically simply in our real-time reaction to watching depictions of our childhood,” Romvari tells me.

Exploring the difference between still photographs and moving footage in terms of processing and our emotional responses, Romvari recalls: “My father’s photography, which I had never seen in full prior to filming, made me cry – it devastated me. The video footage that shows me and my brothers playing captures such purity – those made me laugh! They were a delight.”

The filmmaker masterfully uses the visual allegory of developing photographic prints from film negatives to draw similarity between physical images and trauma. Memories that might be blurred or hazy in the mind can be clarified in reality through direct confrontation – just as chemicals react with film, dealing with trauma is to process the memory of it. As Romvari explains: “Filmmaking can allow for a type of substitute of memory, to fill in the blanks. I wanted to piece things together from my past in a visual way, while also connecting the dots into some kind of narrative structure that might help me make sense of it all.” For Romvari, filmmaking can be a means of restoring agency to the survivor.

In making the film, Romvari referred to Marianne Hirsch’s theory on photography and trauma to investigate the psychology behind her emotional response to the images, as well as essays by Susan Sontag and Roland Barthes. It was reading Barthes’s Camera Lucida that first made me reflect on why certain images affect me more than they may affect others – an experience of what Barthes calls “punctum”, of being “stung” or “pricked”. What pricks us makes us bleed, but it is subjective – what triggers something in one person might not leave an impression on another. In these cases, it depends on the traumas we’ve experienced, and how certain visual cues can cause those memories to resurface involuntarily.

The photographic metaphor central to Still Processing is similarly used in Pieces of a Woman, written by Kata Wéber and directed by her partner Kornél Mundruczó. The film opens with an unbroken, half-hour long shot of a troubled home birth. We experience the trauma as closely as cinema allows, due to the omnipresent camera and Vanessa Kirby’s shattering performance as Martha. While everyone else tries to convince her that the best thing to do is to prosecute the midwife, she ultimately realises she has to confront the memory of the event to move on. She develops the photos her husband took of her holding her child before she died, and starts to process the tragedy.

This takes time. Martha starts smoking again, arguing with her family, locking herself in her bedroom. Trauma manifests in different ways – it can change who we are and make us lose our sense of self. We’ll try to manage it as best as we can, maybe through drugs or alcohol, often to the detriment of our physical health. Pieces of a Woman shows us that this is okay, normal even, but that it’s only a short-term means of control. Both Wéber’s screenplay and Romvari’s direction are refreshingly personal. That Still Processing and Pieces of a Woman use the same metaphor of developing photographs to process mental trauma feels more than just a coincidence. These films are about women finding effective visual language to communicate their own experiences, and in so doing, providing others with a new means of expression. To define our traumas, rather than allowing our traumas to define us.

It took two years for me to find the language with which to talk about the traumas I’d experienced. But when I finally did, every time I discussed it out loud I felt more in control. What shocked me was that, after telling my close female friends, they would share their own experiences of sexual assault, many of whom hadn’t felt able to report it. Figures for unreported campus rapes are staggering – the American Civil Liberties Union estimates that around 95 percent of campus rapes in the US go unreported – and everyone seems to have heard at least one horror story that stops them from doing so.

This is what another 2020 festival release, Emerald Fennell’s Promising Young Woman, gets so right. The trauma that compels Cassie to scare the shit out of any man vile enough to prey on a drunk woman does not stem from a direct assault on her, but from her friend Nina who was raped at a med-school house party. Cassie’s revenge isn’t initially on the man who assaulted Nina, but rather on those who sought to silence her, who did not believe Nina’s experiences were criminal, for the sake of reputation and profit: the defendant’s lawyer, the college dean, her classmates.

The gaslighting that brought Nina to end her life is the trauma Cassie finds impossible to move on from and start her own life. Despite setting itself up as a model for female empowerment, Promising Young Woman can appear to be pessimistic. For Cassie, confronting her trauma only reaffirms that the past can never be undone. Fennell’s film serves justice to the perpetrators, but denies its female characters the release which processing memory can offer. Maybe that’s because not everything can be accepted, and not everything that hurts us can, ultimately, make us stronger. And it’s vital that we see that’s okay.

The women in Still Processing and Pieces of a Woman show two ways in which we can come to live with trauma. Promising Young Woman, on the other hand, shows the realistic challenges many still face. I, like too many others, am grieving during the COVID-19 pandemic. What these films offer as a triptych is the impression that there is no one right way to come to terms with loss. It’s messy, painful, and uncertain. Perhaps in these troubled times, these films are reassuring in their promise of being able to overcome grief and trauma – even if it takes time.

Lillian Crawford (@lillcrawf) is a writer on all things film, culture and gender. Her musings can be found at Little White Lies, Letterboxd and Varsity.