Fleeing manipulative men and reconnecting with themselves, Thelma and Louise are two heroines reclaiming their desires and using language as a weapon in Ridley Scott’s seminal road movie. Hannah Holway writes on the film’s subversive, galvanising power.

I was 17 when I first watched Thelma and Louise. Studying film, I saw all the movies I felt I should be watching: Kubrick, Scorsese, Hitchcock. They were the greats, the classics, the blueprint for any future cinematic success. They were all men’s stories. When women did appear, they were love interests, mothers, plot devices – and they weren’t around for long. Soon after being shown Thelma and Louise in class, I would learn about the Bechdel test, the measure of women characters’ representation in the industry I was falling in love with. But when I watched Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon driving a turquoise 1966 Ford Thunderbird from Arkansas to New Mexico, I was struck. These two women had their own histories, their own agency. The men were, for once, secondary to their narratives.

From the opening shot of Ridley Scott’s 1991 road movie, Thelma and Louise are three-dimensional. In a montage sequence, Louise bags up her clothes for a trip away, while Thelma dumps the entire contents of her wardrobe into a suitcase, hangers and all. Louise’s type-A personality is protected by a steely exterior, while Thelma is naive and exudes chaotic energy. Immediately, their dynamic friendship feels clearly lived-in. In Louise’s Thunderbird, they set off from mundane lives in Arkansas – Louise a world-weary waitress, Thelma a stay-at-home wife – for a weekend at Louise’s colleague’s holiday home. When Thelma is attacked and almost sexually assaulted at a bar by a sleazy local, Harlan Puckett, Louise shoots and kills him. Knowing the slim chance of a fair trial after people would have seen Thelma dancing with Harlan all night, the women embark on a runaway journey across Southwest America that sees them go from unassuming citizens to, as Thelma says, “regular outlaws”. They refuse to continue being humiliated and undermined by the men around them, taking drastic measures to protect themselves against the harsh environments they have so far accepted as the norm.

Aside from being the first film I’d seen in which women had their own compelling backstories and character arcs, Thelma and Louise portrayed a female desire that I was yet to see represented. I’d seen men desire women on screen for years: in Vertigo, I watched James Stewart lust after Kim Novak, the act of his looking something she had no choice in. The camera singled out features of the female body, imbuing them with sensuality so they no longer really belonged to the woman. But in Thelma and Louise, it’s the body of a young Brad Pitt, in his breakthrough role, that the camera worships. Playing young hitch-hiker and petty criminal J.D., Pitt’s bright blue eyes, dimples and floppy hair immediately position him as an object of lust, as Thelma literally trips over him while leaving a phone box. After she watches him walk towards her through the wing mirror, Pitt is shown on the right side of the screen, with only a section of his body visible. Instead of Davis’ body being compartmentalised, it’s Pitt’s. When Thelma asks Louise “Did you see his butt?”, she places herself as the voyeur. Not only is she unashamed of her desire, she has autonomy over it.

As women, we realise from a young age that our bodies don’t really belong to us. When objectified, sexualised and harassed, women learn in these moments that the person attached to the body is irrelevant. I was ordered to “cover up” on a school trip when I was 13; informed that my body was changing in inappropriate ways, before I even noticed the changes myself. In later years, the girls in my school would be told repeatedly that the length of our skirts were distracting the boys in our class. Thelma experiences a violation, a fear that many women know all too well. Harlan doesn’t care about her, but he does feel entitled to her body. The scopophilic gaze of the camera in Hollywood films has long confirmed that the female body can be separated from the woman who owns it through fetishising angles and close-ups: as film critic Christina Newland states, “Women have rarely been allowed to be on the other side of this equation; to be effusively desirous”.

When my friends had their first sexual experiences, it was because their boyfriends wanted to. As women, we didn’t know how to outwardly express desire; no one told us it was okay to do so. In openly desiring J.D. – persuading Louise to give him a ride by pouting her lips and whimpering, before panting like a dog when she accepts – Thelma becomes liberated by her sexuality, a previous source of repression. The camera follows Thelma’s lead: we are put in her position, our eyes fixed on Pitt’s body as he saunters away, bag slung over his shoulder, the epitome of cool. For the first time, I felt aligned with not only a female character, but with the film entirely.

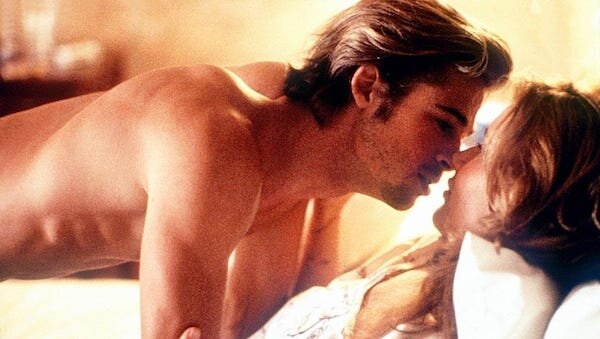

Later, when J.D. comes to Thelma’s motel room in the rain, the audience already knows what’s to follow. Interspersed between shots of Louise’s break-up with on-off boyfriend Jimmy in the next room, each scene of Thelma and J.D. ramps up the tangible sexual tension, from his top disappearing without explanation, to his re-enacting of the upbeat liquor store robberies he’s currently on parole for. As the sex scene begins, the camera pans from his undone jeans, across his chiselled torso and to his equally carved jawline; in a direct subversion of the heterosexual male gaze which Laura Mulvey states characterises women by their ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’. Here, Pitt is the ‘spectacle’, and Thelma, alongside the audience, ‘the bearer of the look’. Thelma and Louise showed that it was possible for men to be passive objects of a female desire, and for women to project this desire without shame or degradation; not only through a literal reversal of the gaze, but through the language used and reused by the characters.

It’s certainly not lost on me that the film which showed me a first glimpse of the possibilities of female representation on screen, was directed by a man. But it’s Callie Khouri’s screenplay that lent a voice to my stifled thoughts, by giving the women the power to tell their story through reconstructed language. In Thelma and Louise, language is repeated, twisted, given new meaning. The men consistently call the women ‘crazy’ – a word inextricably connected to femininity ever since female hysteria was a common diagnosis in the 17th century – but in Khouri’s screenplay, ‘craziness’ is reclaimed. ‘Mad’ women have long been a staple in art. Cinematically, they have always been linked to sexuality, with Glenn Close’s ‘bunny boiler’ Alex in Fatal Attraction suggesting the seemingly catastrophic consequences of a woman overtly showing desire. Watching J.D. walk away from the car after Jimmy arrives, Thelma quips “I love to watch him go”, before Jimmy suggests that she “take a cold shower” in response. Thelma teases “You know me Jimmy, I’m just a wild woman”; her ostensibly newfound ‘wildness’ allows her to project an unabashed desire for men. The next day, giddily showing off a hickey to Louise after her night with J.D., she manically exclaims “Well, I’m not on drugs, but I might be crazy!” By reframing ‘craziness’ as a liberating emotion, Thelma subverts the idea that female sexuality and ‘hysteria’ should be sources of fear.

Throughout the film, men consistently downplay and underestimate the women by passing off their emotions as signifiers of instability. When Harvey Keitel’s Hal, the chief detective following Thelma and Louise’s case, asks Darryl if he’s close to his wife, he responds, “I’m ‘bout as close as I can be to a nutcase like that”; a statement met with a knowing laugh from Hal. I’m reminded of my younger self, navigating the intensity of first crushes or the intimacy of my first romantic relationships, and the countless occasions I heard boys around me using the term ‘crazy’ for a girl who texted back too quickly, who showed her emotions too easily. It’s shorthand for an unquestioned dismissal of the nuances of sensitivity. Later in the film, after finally confronting a truck driver who had been making lewd gestures at them, Thelma and Louise trick him into pulling over and talking to them, so that they can blow the tires of his truck. He tells them “You women are crazy!”, to which Louise replies, “You got that right”. Rather than feeling shame around the word, the women reclaim it, finding freedom in escaping expectations placed on them by the men in their life. It took me a long time to realise that men dismissing women’s emotions as ‘crazy’ didn’t mean that they were emotions worthy of humiliation. When Thelma reminisces on the drastic change in her from mere days before, Louise warmly tells her, “You’ve always been crazy, you’ve just never had the chance to express yourself”.

Thelma and Louise also reuse language between themselves; when Thelma admits that she hasn’t asked Darryl’s permission for the trip, Louise exasperatingly asks her friend, “Is he your husband or your father?” When Thelma speaks to Darryl for the first time on the road, she finally stands up for herself with Louise’s words: telling him “You're my husband, not my father”, before a scathing “Go fuck yourself”. As well as their own words, the women rewrite cultural and traditional language, disrupting the societal expectations connected to certain terms, particularly those used around disbelief. When Thelma wants to report Harlan to the police, Louise screams at her “Who’s gunna believe that?” After inadvertently learning from J.D., Thelma later robs a convenience store at gunpoint – literally repeating the language that J.D. taught her – as the film cuts to Hal, Darryl and other male detectives watching CCTV footage of the robbery in stupefied disbelief. The Thelma that Darryl left for work two days before is proving his preconceptions of her wrong before his eyes. Thelma tells Louise, “It was like I’d been doing it all my life… nobody would believe it”.

Rather than stay confined to the ways in which men disbelieve, distrust and undermine them, Thelma and Louise choose another avenue. Language is critical: when I first saw Harlan tell Louise that he and Thelma were “just having a bit of fun”, I’d already heard the boys around me use the same wording to describe instances of sexual harassment. In challenging, rewriting and reclaiming the language commonly used around their oppression, the women in Thelma and Louise taught me that disrespect and belittlement weren’t always simply inevitabilities for women.

Nearly 30 years after the film’s release sparked both controversy and praise, change in the industry has been simultaneously monumental and painfully slow; while there is a wider variety of women’s stories to choose from today, the omission of female filmmakers from this year’s BAFTAs and Academy Award ceremonies speaks for itself. Watching Thelma and Louise at 17 sparked a desire in me to seek these stories out, to ensure I wasn’t just watching the same narrative replayed over and over again. But more than this, it assured me that I didn’t have to endure what I had so far accepted. Trusting in and showing my emotions didn’t necessarily equate to ‘overreacting’; women could desire men in the same way as men desired women. As Thelma and Louise do in the film, I gained the confidence to reclaim, and learn the power of, language and desire. To remove this film from my life would be to leave a gaping hole where it fits into my being, my perception of who I am. Without it, and the ways it taught me about film, women, and myself, I wouldn’t be the same person.

Hannah Holway (@HolwayHannah) is a Film Studies graduate and film writer from London. She loves women in horror, coming-of-age films and Black Mirror, and can be found writing about these and other things at Flip Screen, Talk Film Society, Hero and more.

.jpg)