Conversion therapy camps still loom large in many countries – which is why the education and appreciation of queer cinema from authentic perspectives has such crucial value. With its kitsch and cutting satire, Jamie Babbit’s debut But I’m A Cheerleader remains a touchstone title for Megan Wilson – here’s why.

Growing up gay in the digital age was not without challenges, but the internet connected me to queer cinema that was, and continues to be, a life-saving source of comfort in the times I felt isolated. And yet – I often wondered why so many films depicted lesbian love as either doomed affairs or forced romantic comedies. This is largely, I realise now, because these films weren’t made by someone like me, or even for me. But then I stumbled upon But I’m a Cheerleader, a budget screwball comedy about a young girl sent to a conversion therapy camp named True Directions to cure her latent lesbianism. Here was the answer to my prayers – a film that doesn’t gloss over the targeted oppression suffered by queer people, but at the same time never reduces its subjects to hopeless victims. Instead, the film takes a satirical and campy approach to the coming-out narrative, with an authentic sense of queer cultural knowledge that only a lesbian director could bring.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of Jamie Babbit’s debut feature But I’m a Cheerleader, which remains the filmmaker’s most popular and oft-quoted work to date. The film’s cult status amongst lesbians can be attributed to its self-reflexive comedy, timeless camp aesthetic, and deft critique of oppressive structures. Babbit takes conversion therapy – a concept rooted in the psychological trauma and violent repression of queer identities – and spins it into a kitschy, almost surrealist vehicle for tongue-in-cheek comedy. True Directions becomes a symbol of the warped American Dream, one that would have its young people moulded into upstanding moral citizens at the cost of their freedom of expression. Instead of exploiting the suffering of LGBTQ youth, But I’m a Cheerleader empowers us through incisive humour, providing a surprisingly shrewd critique of the hetero-patriarchal power structures that be.

Megan Bloomfield (Natasha Lyonne) has it all – a pretty face, a good Christian family, a hot boyfriend, and a spot on the varsity cheerleading squad. She just so happens to also spend a significant amount of time daydreaming about her teammates and their short skirts. Megan’s perfect world comes crashing down when she comes home to an intervention: her conservative parents are sending her to rehabilitation camp because they think she is a lesbian. Megan doesn’t think of herself as gay, but her friends and family have spotted the warning signs: her vegetarianism (“You’ve been trying to make us eat this… tofu”), pictures of bikini-clad women in her locker, and a passion for folk rock singer Melissa Etheridge. Megan is forced to finally reckon with her true feelings, and navigate the volatile journey to a “cure”.

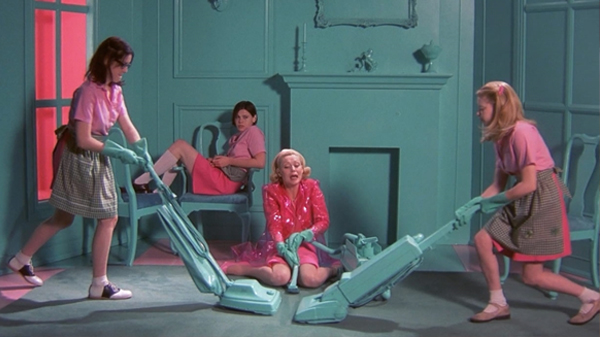

There is nothing straight about True Directions – the moment Megan meets recruitment officer and “ex-gay” Mike, played by drag queen RuPaul Charles, the audience knows that conversion therapy is a doomed endeavour. When Megan arrives at the camp, she finds herself facing a life-sized Barbie Dream House decked out in shiny plastic blues and pinks – a nightmarish vision of binary heterosexuality. True Directions, headed by the contrarily austere Mary Brown, peddles a fool-proof five-step programme that claims to cure its graduates of their homosexuality by reconnecting them with their “correct” gender identity, and simulating happy heterosexual matrimony.

The all-important “root” – a concept invented by the True Directions counsellors in order to explain away same-sex attraction – aims to expose the falsity of gay and lesbian identity by attributing the feeling to an external circumstance. Whether it’s “my mother got married in pants”, or “I was born in France”, every root is itself embedded in the absurd conviction that something confusing or traumatic in your childhood turns you gay. Abhorrent beliefs such as these would seem loathsome to any self-respecting lesbian, but Babbit wants us to laugh. The most effective coping mechanism against oppression is to reduce it to a thing that is too insignificant to harm you. Instead of shielding lesbian audiences from homophobia, But I’m a Cheerleader emphasises it to the point at which it exposes itself as completely delusional – and thus can only become humorous.

The garish colour-blocking of True Directions – where everything from the twee bedspreads to the puritan uniforms completely matches – achieves its camp aesthetic by being at once vomit-inducingly tacky and utterly sincere. To this day, gender roles are so often reduced to a ubiquitous blue vs. pink binary, epitomised by the growing trend of gender-reveal parties in the US. The aggressively gendered production design of True Directions reveals how deeply entrenched these arbitrary signifiers have become in societal consciousness. It’s one of the first “rules” of the gender binary that we learn as children; pink is for girls, and blue is for boys. No questions asked.

When it comes to interrogating gender roles, But I’m a Cheerleader has an overt critical sensibility, akin to the work of queer theorist Judith Butler on performativity. She asserts that, in a hetero-patriarchal society, “doing is being”, and thus gender is inscribed upon a body by a series of copied and repeated behaviours. But I’m a Cheerleader both incorporates and exposes the instability of this view – “reorienting exercises” such as washing dishes and learning to care for a baby are associated with innate womanhood, which in turn urges an attraction to men. However, Megan’s inability to complete the programme and assume her role in the heterosexual order reveals the impossibility of True Directions’ goal. The first mistake Mary Brown and many others make is to conflate gender identity and sexuality. Megan is already objectively feminine in her sense of style and behaviour, but it doesn’t make her any less of a lesbian.

By encouraging us to laugh at the idea that an affinity for tofu could be equated with a desire to have sex with girls, Babbit’s film bolsters lesbian viewers and acknowledges the tediousness of constantly having to defend your identity. Instead, Mary Brown and her militant heterosexuality become the laughing stock – she can’t even recognise that her own son, Rock, is about as straight as a circle. Despite the very real horror of conversion therapy, which is still legal in the US, UK, and many other countries, But I’m a Cheerleader acts as a comforting affirmation that those who deny queer identities are desperately clinging to a vision of a world that does not exist, and that never has. And as Megan begins to fall in love with Graham, another girl at the camp, Babbit tends to their romance with a genuine sense of intimacy that dispels any notion that these feelings could simply be “reoriented”.

My unwavering affection for But I’m a Cheerleader is twofold; I can switch off, laugh at trivial jokes and enjoy a credible lesbian love story – but I can also engage from a theoretical perspective and examine my own relationship with gender roles and queerness. I know this is a film that has my best interests at heart. Too many lesbian films profit from our pain, and render our romances as doomed melodramas. This is art that speaks to the women it represents, hearing their struggles and responding with affirmation and familiarity. Whenever anyone asks me where they should start with lesbian cinema classics, But I’m a Cheerleader will always top my list of recommendations – if only so that I have an excuse to revisit it myself.

Megan Wilson (@bertmacklln) is a freelance film journalist and assistant editor at Screen Queens. She loves cats, critical theory, and Carol (2015).

READ ME is a platform for female-led writing on film commissioned by Girls on Tops. Louisa Maycock (@louisamaycock) is Commissioning Editor and Ella Kemp (@efekemp) is Contributing Editor.