Romantic love is so often understood and celebrated exclusively as something to be shared – but what about those of us who feel all of these emotions on our own? To mark the release of the final chapter in Jenny Han’s To All the Boys trilogy, Anahit Behrooz looks back on the first film in order to make peace with those unrequited, but still self-sufficient feelings that define the most tender part of ourselves.

2020 was, in every conceivable way, the least romantic year of my life. As the initial weeks of lockdown stretched into unending months – fearful social distancing translating into an absence of contact so comprehensive I wanted to scream – I found myself elegiacally turning over past romances in my head, pressing them hard in my hands for every drop of intimacy and connection now so markedly absent. Half-forgotten flirtations jostled alongside half-imagined touches, a year’s worth of frustrated desire leaking into previous, half-healed heartbreaks. I felt wistful, nostalgic for the electricity of it all, the hope and the possibility and the awful, gut-wrenching disappointment.

Because love is, so often, disappointing; painful school crushes that are laughed off, infatuations in your twenties for all the wrong people who can’t or won’t love you back. I can count the number of times I have fallen in love on one hand, but I can count the number of times it has been reified into a traditionally recognised relationship on one finger. But what of those other times? Where does the longing, the sentimentality, the desperation of love go without the socially constructed narrative of coupledom to catch and contain it? What happens to those churning, life-altering emotions, rendered invisible because they only go one way?

It is perhaps this question that has made me turn again and again to Susan Johnson’s To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before, an adaptation of the Jenny Han novel about 17-year-old schoolgirl Lara Jean Covey, whose secret love letters to her high school crushes accidentally reach their hands. Released on Netflix in 2018 at the height of the rom-com renaissance, To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before ticks all the boxes expected of the genre’s regeneration: a diverse cast, subversion of familiar tropes, and smarter, more feminist politics.

But Johnson also took a more expansive approach to what the process of falling in love looks like, articulating the palpable intensity of unrequited love and validating its authenticity in a culture that demands the due processes of dating, monogamy, and happily ever after. In her collected essay collection Intimacy, Lauren Berlant discusses the structures of requited coupledom that delineate contemporary conceptualisations of intimacy, arguing that “[t]hose who don't or can't find their way in that story – the queers, the single, the something else – can become so easily unimaginable, even often to themselves.”

Of course, To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before is a romantic comedy and so does end in a happily ever after – and a heteronormative one at that. Yet it also makes imaginable, even visible, the acts and sentiments of intimacy that precede and sometimes preclude the couple narrative, charting Lara Jean’s growing ownership over her unsolicited desires, and bringing real emotional weight to the concept of the unrequited crush – a concept I thought would be a relic of my teenage years, and has been anything but.

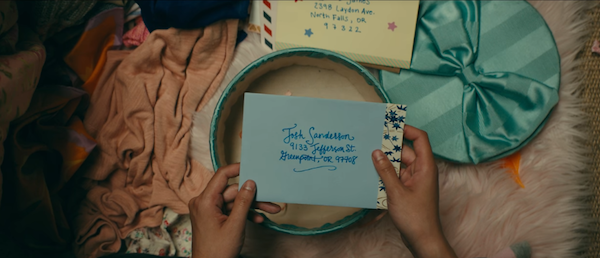

When the film begins, Lara Jean’s emotions play out largely in hypothetical form. Fantasy sequences in vibrant technicolour distance her from the veracity of her own desires and unsent love letters work to cork up the enormity of her feelings. The letters are her “most secret possessions”, each dense with an uncensored, adolescent desire (“I lie awake at night and imagine running my fingers through your hair, feeling your strong arms...”) that plays out across the page.

“I write a letter when I have a crush so intense I don't know what else to do,” Lara Jean explains. “Rereading my letters reminds me of how powerful my emotions can be, how all-consuming”. Her voice is low and intimate, her words quiet and sure. To herself, Lara Jean can easily acknowledge the tangible ferocity of her romantic inner life, “just as long as nobody else knows about it”. Yet in replicating the first-person narration and dwelled-on fantasies of Han’s novel, Johnson carves out an empathetic space for these feelings that belies Lara Jean’s own pre-emptive dismissal, revealing the complex interiority that lies behind these crushes and emphasising their legitimacy as a form of romantic desire.

Watching Lara Jean squirrel away the letters and her dizzying emotions in a small fabric box, I can’t help but think of my own relationship with my romantic feelings, and the furtive, secret ways in which they have so often played out. I think of all the boys that I have loved – or perhaps not the boys themselves, but the hot shame when my feelings towards the boys don’t work out, or even worse, aren’t recognised at all. And I think of the insidious, pernicious narratives that women are told over and over again, cloaked in disgrace and humiliation, that their romantic and sexual lives are only valid if someone else unlocks them, that their feelings are only conceivable in the public imagination if they are reciprocated.

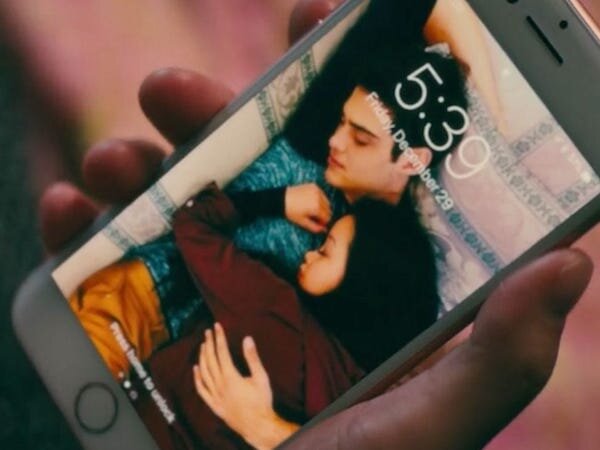

But unrequited love is, of course, a desperately real and authentic form of love, and not simply a ghostly imitation of a socially approved relationship. And it – like all forms of love – should not and cannot remain unimaginable. Eventually, Lara Jean’s letters are posted out by her mischievous yet well-meaning younger sister. Lara Jean enters into a mutually beneficial fake relationship with one of the recipients, Peter Kavinsky, in order to prevent an awkward fall out with her older sister’s ex-boyfriend Josh, and – as the wonderful fizz of adolescence would have it – falls (back) in love with Peter. And after numerous misunderstandings and teenage shenanigans, the film ends with Lara Jean and Peter kissing in a lacrosse field.

Yet Lara Jean’s happy ending is not found in that final kiss. It takes place just before, as she finally admits to Josh how she once felt about him, and then marches determinedly across the field towards Peter, a new letter clutched in her hand, taking agency over her feelings with no expectation of reward. She initially asks Peter to turn his back to her, embarrassed, but moments later taps him on the shoulder, looking in his eyes as she says “I need you to know that I like you, Peter Kavinsky”.

The camera stays on her face, Johnson framing this as a moment of emotional catharsis that has nothing to do with the boy standing in the field, and everything to do with the way in which Lara Jean, hesitancy and certainty colliding in her voice, renders audible and visible her long-suppressed desires. Notably, she does so moments after speaking to Josh about her changed feelings for him, thereby setting a precedent that legitimises her affections through acts of expression rather than reciprocation. Lara Jean even makes to turn away, the purpose of her journey completed, before Peter catches her. “Don’t I get to say something?” he asks. He does, of course, and it’s beautiful. But it’s also not the point.

Through Lara Jean’s final confessions, Johnson depicts a version of romantic love predicated on self-worth and self-sufficiency, and is all the more enviable for it. Gone are the rom-com heroines of old – Sleepless in Seattle’s Meg Ryan stalking Tom Hanks after hearing his voice on the radio, How To Lose A Guy in Ten Days’s Kate Hudson entering into a mean-spirited relationship with Matthew McConnaughey – who needed the happy ending of reciprocity because no other emotional arc was afforded to them. To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before makes the act of being in love, rather than being loved back, its tender core, and in doing so expands our definitions of what intimacy and connection look like – and how they inform not only our relationships with others, but also ourselves. And as 2021 unspools, another year bereft of “real” romance, I will take comfort in the intensity of my crushes and quiet loves that are, as it turns out, so very real after all.

Anahit Behrooz (@anahitrooz) is an arts journalist based in Edinburgh. She currently works as events editor at The Skinny, with words in The List, The Skinny, and Culture Trip. She likes beautiful films about women, old bookshops, and Dan Levy’s eyebrows.

.png)