TW: sexual assault, self-harm, suicidal ideation

While many talk about how films and TV shows addressing sexual assault are “necessary” in light of the #MeToo movement, the works of Emerald Fennell and Michaela Coel are radical in how messy, angry, hilarious and heartbreaking they are. On the occasion of the UK release of Promising Young Woman and almost a year since I May Destroy You, Hannah Strong reflects on her past few months coming to terms with her own sexual assault and her gratitude for Fennell and Coel.

When I was little, my mum used to listen to music while she made Sunday lunch. She had all these compilation CDs, and one of them had PP Arnold’s version of ‘Angel of the Morning’ on it. I always liked the chorus, that rhapsodic way she sang, “Just call me angel, of the morning, angel”. I didn’t have a clue what it meant when I was 11; I don’t think I even clocked the sadness in the line “Then slowly turn away from me”. When I was about 15, I watched Girl, Interrupted for the first time and heard Merrilee Rush’s version of the song playing on the radio while the girls expressed frustration with their treatment in a psychiatric ward. Maybe I should have taken that as a sign; 13 years later a doctor diagnosed me with Borderline Personality Disorder. She put me on an eight-month waiting list for psychotherapy and said my GP could increase my antidepressants for me, before ending the call.

**

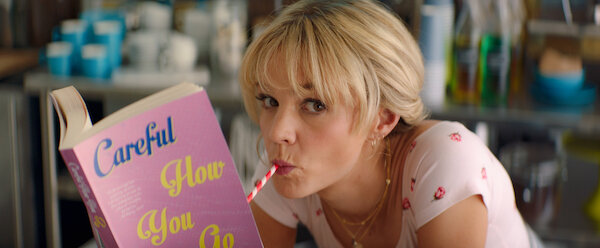

In January last year, before everything went to shit, I sat in an empty screening room with a colleague and we watched Promising Young Woman for the first time. I felt sick and angry and euphoric. By the time Juice Newton’s cover of ‘Angel of the Morning’ played, I knew the film meant something to me. I also knew people were going to hate it. I convinced myself that it was okay, that I was old enough to be completely fine with any criticism and not feel like I, a person with no involvement in the film itself, had any skin in the game.

But the longer I sat with the film, the stronger my feelings became. I tried to unpack what it was about Promising Young Woman that had resonated with me so strongly; surely not the Paris Hilton needle drop or the bubblegum pink aesthetic, which I’ve admired on my Instagram Explore page a million times despite knowing I lack the delicacy to pull it off? I started to interrogate my own experiences with men: all the ‘nice guys’ who had touched me without permission, or called me a frigid bitch when I hesitated to engage around physicality; the boys I met at university who spoke about women they fucked like they were inanimate objects. The one who told a girl he was sleeping with on a regular basis to get an abortion, and then refused to go with her to the appointment. The older guy I met at a stranger’s house party when I was 16 who said “Okay” when I said “No” and then did it anyway. I was drunk, so I didn’t say anything else. I told myself it was fine. It was whatever, something that just happens to girls, no big deal. I was so desperate to be the cool girl, the easy-breezy down-for-anything one all the boys liked. I managed to convince myself this was all part of life’s rich tapestry.

My mental illness has erased a lot of my memories, perhaps as an act of self-preservation. It took Promising Young Woman to cut through the static in my brain, forcing me to confront a reality I didn’t accept as my own. I rationalised there wasn’t a name for it 12 years ago. It was just something that happened.

**

I never, ever, ever wanted to be the victim. To me that sounded like another form of sickness, and I already knew too much about that.

**

Talking to my housemate and her friend a few weeks after that cinema trip, we somehow ended up comparing the first time men exposed themselves to us. “It happened a lot on the metro, when I was a teenager,” she said, very matter-of-fact. “Our mothers just told us to ignore it.”

**

I had been trapped inside the house for a month when Fiona Apple’s ‘Fetch the Bolt Cutters’ came out, but it felt like longer. I was starting to climb the walls. No amount of performing sanity for Zoom quizzes or attempting haphazard crafts learned on YouTube could paper over the cracks. I started baking obsessively, and tweeting into oblivion every single asinine thought that crossed my mind. I became obsessed with that one line:

Fetch the bolt cutters, I've been in here too long

More lucid people than I have written passionately and intelligently about Apple’s songs, about the myriad ways the industry fucked her over, about the radicality of her fifth studio album and how searing her lyrics are. The way they speak to contorting yourself to fit an image other people produced for you; playing nice and waking up years later with this primal anger inside that you can’t figure out what to do with. Realising the real fucked up shit that happened when you were younger was, in fact, real fucked up. That dull, persistent ache deep inside; the one that asks “What now?”

**

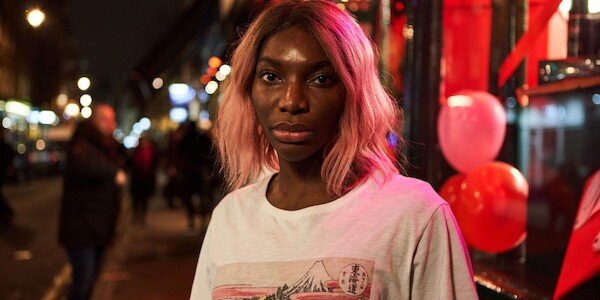

I started watching Michaela Coel’s I May Destroy You in the summer, around the same time I started cutting again. I felt the same way I had after watching Promising Young Woman. I waited two weeks to watch the finale because I didn’t want it to be over: it felt like the series finishing was severing some sort of connection I had with Arabella, who was so angry and so sad and so funny and so smart and so lost, this crystallisation of grief and rage that I needed to see so desperately in order to understand what the fuck was going on with me.

I called the crisis team and told them I wanted to die. They told me I’d have to wait for a psychiatrist assessment if I wasn’t “in any immediate danger”. I said okay. “That’s fine.”

**

It's now been 16 months since I first saw Promising Young Woman. I’ve read a lot about it in that time; I’ve had arguments with my friends, I’ve seen criticism that I agree with and some that makes me feel like I’m a shitty, stupid person for not only relating to but actually loving the film. Even so, while writer-director Emerald Fennell and Carey Mulligan are heralded for their ‘take on the rape-revenge thriller’ I can’t help but think that’s not the film I watched at all.

When I think about ‘rape revenge’ films I think about I Spit On Your Grave, Revenge, MFA, American Mary, Hard Candy; films about women who ensure men get their just desserts, who make them hurt just as much as they deserve. I think about the unofficial ‘Good For Her’ pantheon: Carrie, Midsommar, Ready or Not. Women who emerge bloody and victorious and half mad from the trauma.

Is what Cassie does, “revenge”? Her best friend is dead; no amount of lecturing men will change that, or likely even make them think twice before they try to fuck a drunk girl. Concerned onlookers orbit her: her parents, her boss and friend Gail, and Nina’s own mother tells Cassie she needs to move on. But Cassie’s mission isn’t about justice, even if she has convinced herself it is: putting herself and other women in danger demonstrates her instability. We’re never meant to cheer Cassie on or support her in fooling other women into thinking they have been raped or that their daughter has been abducted. She wants everyone else to hurt as much as she does. And when she realises the futility of her course of action, she self-destructs.

The film’s final act of cruelty – an unflinching scene of violence in which Cassie is murdered by the same man who raped her best friend – reflects the horrific reality of sexual assault; people pay more attention to a dead girl than a raped one. How many women have to die before anything changes?

It’s telling that Promising Young Woman ends with law enforcement swooping in, as we’ve been conditioned to believe they will. I don’t see this ending as a victory for Cassie and Nina, or for the audience – I see it as the continuation of a cycle. Rich white men, circumstantial evidence, Cassie’s only ally a lawyer (already proven a coward) who spent his career getting rapists off the hook; those are poor odds. The chances of “justice” don’t exist in Promising Young Woman any more than they do in real life.

Universal wanted Promising Young Woman to be a barnstorming rape revenge thriller, and the marketing sells it as such. A lot of critics have praised the film in the same way. But all I see is two dead girls and a horrific sense of deja vu. It’s a film about grieving and constructed realities; lies we tell ourselves and lies we’ve been told over and over by other people.

The police are here to protect you.

Boys will be boys.

She was asking for it, drinking that much, dressing like that.

Fennell’s aesthetic choices – the sherbert colour palette,the whimsical costuming, the carefully curated playlist of familiar ballads about romance – only serve to heighten my perception of Promising Young Woman as a fantasy, where even the most timid form of restitution is unobtainable. That’s why I love the film; because so often the dream outcome looks like blood and guts and gore. This time it just looks like the bare minimum, an acknowledgement of wrongdoing. How fucking bleak is it that can be positioned as a pipe dream?

**

In ‘Ego Death’, the final episode of I May Destroy You, Arabella fantasises about all the ways she could make her rapist suffer for what he did to her. There’s the classic bloody revenge fantasy, a version in which she confronts him in order to understand what he did, and one in which they have consensual sex – all three reminiscent of the sort of narratives we’re used to seeing in media about sexual assault. (I recommend Angelica Jade Bastién’s incredible analysis of this episode, and her writing on the series in general.) We never learn which path Arabella takes in the end, if any, but in the episode’s coda, we learn she’s written a book about her experience, dedicated to her best friend, Terry.

**

Catharsis comes in the realisation there is no catharsis.

**

I’ve been writing thru it for a long time now; divulging the juicy details of my various trauma and psychosis for column inches and some modicum of personal closure. I wonder if I’ve said too much, or if everything I write is just some rebel yell into the endless void of the internet. I wonder what I’m trying to achieve in expressing such intimacy to strangers, and why women are categorically more encouraged to recall their trauma in the name of art.

(I also wonder, hysterically, if it’s putting people off sleeping with me.)

**

I want more stories about the banality of this; the conversation I had in my living room a few months ago about our encounters with flashers on trains, the way women warn each other about the guys who are “a bit creepy” in their wider social circle. The market for straws and lids you can use at bars to stop yourself getting spiked. How you learn to clench your keys in your fist when you walk home, and the reflex of jumping a bit when a man approaches you unexpectedly to ask if you know where the nearest cash point is. This is everyday for half the world, and it doesn’t stop with the shoot-out or the whine of a police siren.

Most of all, I want the film industry to stop patting itself on the back for doing the bare minimum and expecting one film to neatly resolve centuries of fucking up.

**

I used to be so angry all the time. Every day I found reasons to be mad at the world. The thing no one really tells you about living like that is how exhausting it is; how rage drains you, makes you bitter and distant and fragile. I destroyed a lot of relationships with my volatility, let them wither on the vine because I was so deeply unhappy and never really understood why I found it so tempting to self-destruct in new, inventive ways. I think coming to terms with the past has helped me let go of some of that pain – I’m grateful to Emerald Fennell’s film for making that possible.

**

Nina Simone’s cover of ‘Angel of the Morning’ might be my favourite version. There’s a beautiful harp melody that plays as she sings, imbuing the song with an ethereal quality befitting of the title. In every other rendition I hear the melancholy that lurks beneath the soaring chorus, but Simone’s cadence adds a softness that evokes safety. It’s like waking in your own bed to the sunlight peeking through your curtains; walking down the road in your favourite trainers, to the cafe with the nice barista for a flat white and a pain au chocolat.

Allowing yourself a deep breath, and to believe that tomorrow will be a better day, if you can keep putting one foot in front of the other.

Hannah Strong (@thethirdhan) is the Associate Editor at Little White Lies. She is currently writing a book about film and raising one beautiful houseplant. She considers both of these things as equally important.