READ ME is a platform for female-led writing on film hosted by Girls on Tops. Louisa Maycock (@louisamaycock) is Commissioning Editor and Ella Kemp (@efekemp) is Contributing Editor.

Sex and self-realisation go hand in hand for the average teenager – but there’s still some kind of stigma around the thing everyone is trying to lose. Mary Beth McAndrews explores virginity, shame and awkward realities in the teen movies of our collective youth.

Once you have sex, you’re an adult, right? As with Brittany Murphy’s iconic line in Clueless, “You’re a virgin who can’t drive”, the word ‘virgin’ can be hurled like an insult. Virginity: the pinnacle of teenage success is losing it. Being a virgin is a shame that many try to hide, before then wearing its loss like a badge of honor once it has been taken away. This obsession has been captured in films over and over again, from obscene comedies to over-the-top horror films and somber dramas. Regardless of the genre, society can’t stop thinking about virginity and what it means.

For teenage boys, virginity symbolises a lack of masculinity. Boys want to prove their virility, and the best way to do that is through heterosexual sex. In The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love, bell hooks speaks of the rituals of domination that men participate in to assert their own control. The sexual conquests of a teenage boy are an extension of that. Hooks says, “Little boys learn early in life that sexuality is the ultimate proving ground where their patriarchal masculinity will be tested”. What better way to display this strength than by making a spectacle of losing your virginity?

Films such as Judd Apatow’s The 40-Year-Old Virgin and Greg Mottola’s Superbad use this spectacle through characters coded as outcasts, stereotypical ‘nerds’, who, since they are still virgins, are left behind in proving their sexual orientation. In the case of The 40-Year-Old Virgin, Andy (Steve Carell), is ridiculed for taking so long to have sex. Superbad follows a similar route of sexual conquest, but with teenage boys who feel the need to lose their virginity before they go off the college. These are just two examples within a large canon dedicated to the triumphant, often comedic, attempts to finally pop that cherry and prove to just how manly a fictional man can be.

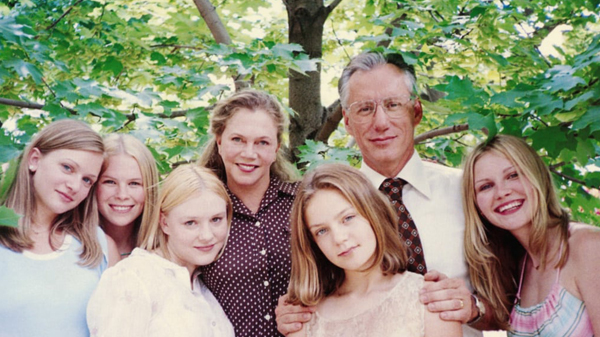

For women, virginity is just as complicated. Instead of determining their sexual orientation, it is meant to act as a sign of innocence, something to be treasured, and coveted only by teenage boys. In Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides, the virginity of the five Lisbon sisters is the only thing that the male narrator can focus on. This purity isn’t just coveted by teenage boys, it is also protected by their hyper-religious parents, who want nothing more than to preserve the purity of their daughters.

However, as the film’s title suggests, this obsession ultimately leads to tragedy. As Jeffers Tamar McDonald says in Virgin Territory : Representing Sexual Inexperience in Film, “Teenage sex is still confusing and often dangerous for those who do it, leading to death in The Virgin Suicides (2000), social mayhem in Cherry Falls (2000), drug abuse in Thirteen (2003), religious trauma in Saved! (2004), and, most consistently, family disintegration in all of these films”. These examples reveal an unnecessarily grim expectation put onto the shoulders of young women, as their mere safety is seen to be at stake if they have sex.

The concept of virginity as we know it has been a socially-constructed tool of shame, when in reality, having sex for the first time is just an awkward life experience that many go through and almost immediately wish to forget. We don’t parade around school declaring that we finally had sex on our parents’ old couch in the basement – or that it lasted 30 seconds. That’s the reality of teenage sex for many, but rather than accept the fact, films often construct something entirely different that colours the perceptions and expectations of a young audience. A film that authentically captures the awkwardness of having sex for the first time is Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird. The coming-of-age tale captures the fear, uncertainty, and struggles of growing up. Gerwig borrows tropes from teen comedies, but makes them more realistic as to effectively capture the difficulties of fumbling towards adulthood.

The sex scene forgoes the usual romantic music and lit candles, instead beginning with Lady Bird, a phenomenal Saoirse Ronan, and her boyfriend, Kyle, played by the moody Timothée Chalamet, just sitting on his bed watching TV, while his parents are presumably just a stairwell away. Lady Bird proudly declares, “I’m ready to have sex,” which seems to adhere to the typical trajectory of losing your virginity in a teen movie: an emotional declaration, only to be followed by a passionate moment of beautiful love-making. But, she’s quickly shut down by Kyle’s aloof, “OK, great.” There is no pastel lighting or wistful teen ballad playing softly. They do the deed and just as quickly as it started, it ends.

The scene isn’t overly serious, but it isn’t particularly funny either. Instead of using Kyle’s stamina as a punchline, they both find themselves in rather compromising and awkward positions as Kyle doesn’t know what to do with his arms and Lady Bird’s nose starts to bleed. Her nosebleed is an interesting inversion of the “virgins bleed after having sex for the first time” myth. Instead of the typical reveal of a bloody sheet, we instead see that Lady Bird is just one of those people who gets unexpected, unrelated nose bleeds sometimes. It is nothing out of the ordinary, just a rather poorly-timed moment.

Lady Bird and Kyle’s post-coital scene also had the potential of falling into typical melodrama, as Lady Bird suggestively strokes Kyle’s chest and points out that they deflowered each other. But the illusion is smashed, as Lady Bird finds out her boyfriend isn’t a virgin, and more importantly, can’t remember his number of partners. She loudly yells, “why wouldn’t you keep a list, we’re in high school!”, which captures the essence of raunchy coming-of-age comedies – teenagers keep a running list of their conquests because they’re young, immature, and want to treasure every potentially transgressive moment of their young lives. But Kyle subverts that image, with a shockingly cavalier attitude towards his own sexual experiences. He asks Lady Bird, “why did it need to be special?” and then telling her not be upset because “you’re going to have so much unspecial sex in your life.” While Kyle is one of those characters that you shamefully remembering lusting after in high school, he also offers the vehicle for some salient points about the inflated importance of virginity and sex. But this doesn’t ease the sting of reality that has slapped Lady Bird in the face.

McDonald explains, “Thus far, teenage sex in American cinema tends to be either frivolously unenlightened or, more often, torturously somber.” But Lady Bird pushes back against that binary. Lady Bird’s first time shows that losing your virginity can be more than just hilarious or desperately serious: it can be fun, emotional, disappointing, underwhelming, and confusing. It can even be frustrating, as Lady Bird knows when she yells, “I was on top! Who the fuck is on top their first time?!” This illustrates how the film navigates those two spheres of hilarity and seriousness at such a turbulent time in a teenager’s life, a life that is so often centered around having that integral first sexual experience. Lady Bird takes a societal obsession and makes it into what it really is: something awkward, normal, sometimes profound, and ultimately unspecial. Gerwig normalizes something that is a part of many teenagers’ lives and portrays the truth of all of virginity’s parts, from its disappointments to its thrills. But in portraying this truth, Gerwig makes sure of one thing: to never discredit butterfly-in-the-stomach excitement of teen love.

Girls on Tops x Little White Lies anniversary edition Lady Bird illustrated GRETA GERWIG t-shirt available here

Mary Beth McAndrews (@mbmcandrews) is freelance writer based in Chicago. She loves all things macabre, and mostly writes about the intersection of horror and gender. She is an editor for Much Ado About Cinema and contributor for Nightmare on Film Street.