Hunger, both erotic and biological, manifests in gloriously delirious ways in Věra Chytilová’s Czech New Wave classic, Daisies. Focusing on the desire and satisfaction of two young women, dismantling the uptight masculinity around them, the film calls for a revolution. Ashley Saville welcomes it in.

Picture this. You arrive at the restaurant – it’s eight pm. You’re seated across from a mysterious stranger, your date. She’s a woman you’ve been talking to on Hinge for a week or so, and have decided to meet for a meal. 20 minutes in, your potential lover is eating with her hands. Burying her fingers into the springy fat and flesh of a rare steak, pink juice drips down her forearms and you count it lucky that she’s wearing short sleeves. She spears a whole potato on the end of her knife and buries it deep in her mouth, its pale and powdery insides exploding across her upper lip. Grinning like an animal, she looks you in the eye and lets out a wild giggle. You’re not sure whether to be revolted or turned-on.

A similar cocktail of confusion, consumption and coquettishness characterises Věra Chytilová’s cult classic of Czech New Wave cinema, Sedmikrásky (Daisies), first released in 1966. 72 minutes of saturated psychedelia and Neo-Dada absurdism, Daisies was Chytilová’s second film and is her most well-known. A student at Prague’s prestigious FAMU academy of film at the end of the 1950s, Chytilová rubbed shoulders with Jiří Menzel and Jan Němec, propelling her into the epicentre of avant-garde filmmaking.

Daisies is a colourful child of the Czech New Wave: dissenting, darkly humorous, and satirising of the communist regime. The film’s chaotic narrative follows a pair of elfin teenage girls, both named Marie, as they embark on a string of mischievous pranks across Prague. From dinner dates with sugar daddies to snacking on sandwiches in a bathtub full of cream, the film culminates in a decadent food fight in which the girls lay waste to an elaborate banquet set for a large group of party officials. The sexual politics of eating and etiquette is a central poetic throughout the film, which was ironically censored by the Czech government upon its release on account of its wasteful display of food. Dedicated in an end-title to “all those whose sole source of indignation is a trampled-on trifle”, Daisies evokes a colourful elision of food, gender politics and erotic desire.

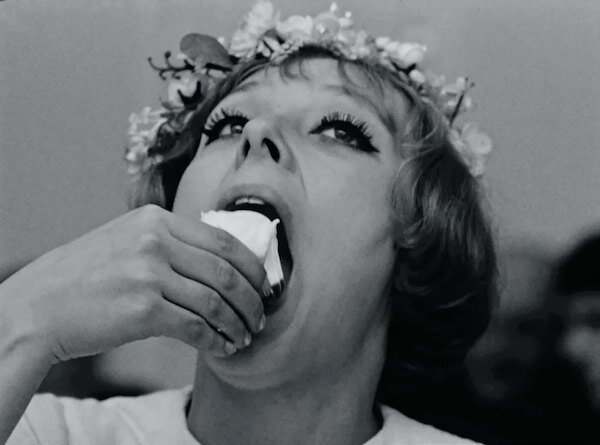

The first display of radical consumption takes place within 10 minutes of the film’s technicolor opening. Transitioning from colour to black and white, we see the dark-haired Marie I (Jitka Cerhová) on a date with a balding older man in a crowded restaurant. Mere moments later, the pair are joined by Marie II (Ivana Karbanová), much to the surprise of the man. When a roving waitress offers the table complimentary slices of cream cake before the arrival of the main course, Marie II’s eyes light up with wild glee. She eats with fierce dynamism, unabashed at the splatters of cream across her lips and cheeks. To the man’s bulging-eyed horror, Marie II chews with energetic swings of the jaw, biting gigantic hunks of bread from the complimentary baguette. She eats an entire chicken with her left hand whilst chain smoking with her right. “I love food. I love eating. It’s delicious,” she exclaims with a full mouth.

A spectacle of mastication, Marie I’s coyness throughout the meal suggests that her friend’s arrival was by no means a surprise. Rather, this early interaction provides a formative moment of queer tension between our two protagonists, escalating thereon. As a viewer, we wonder if Marie II’s id-like disregard for gendered dining etiquette was intended to deliberately humiliate her male company in act of erotic sadism. What’s more, we question whether this behaviour is commonplace for our giggling central double act: a kink, even.

The queering of the patriarchal dynamics of mealtimes is not limited to the pair’s public escapades. Bizarre eating spectacles also take place in private spaces, in which men are absent. Sat on a four-poster bed, the Maries stage a subversive ritual of food preparation whilst listening to a voicemail from one of their besotted lovers. As the anonymous male voice declares his undying love through the telephone receiver, the girls begin to cut up phallic foodstuffs and eat them off long sticks. A pork sausage – pale and fatty – a banana with its skin on, a gherkin oozing green juice: the juxtaposition of fragmented phallic foods with the voice of the desperate male lover provides a moment of castrative physical comedy.

And then there’s the food fight scene, which sees the emancipated female energy crescendo to an orgiastic climax. Their most ambitious prank of all, the Maries sneak into a banqueting hall, lavishly set up for a ceremonial dinner. Initially shot in black and white, the screen is illuminated in vibrant technicolor as the girls sit down to eat. A fast-cut montage soundtracked by the rapid, almost orgasmic noise of the Maries panting allows us to witness the dazzling array of food spread vastly across the table: multi-tiered terrines and glistening meats, devilled eggs and colourful canapés. Tucking a napkin into her dress to catch splattering grease, Marie II takes a platter of steak tartare, mixes the raw egg yolk and ground beef with her hands and sucks the mixture off her fingers. Marie I drives her fingers through the crisped skin of a stuffed poussin and rips the flesh apart with her hands. The scene ends with the girls swinging from a chandelier in wild abandon, treading through food as they gleefully dance on the table. Flouting the asceticism of the communist regime in their hedonism, the display of overconsumption and wastefulness is steeped in satire as well as gender critique.

Chicken and rabbit, sausage and cold-cuts: the Maries’ carnivorous obsession with meat is perhaps the most strikingly gendered aspect of their eating habits. At one point, Marie I even cuts an illustration of a T-bone steak out of a glossy magazine and chews it up. Carol J Adam’s provocative text, The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory (1990) provides an interesting companion piece to read alongside the theme of meat consumption in Daisies. Arguing that meat-eating and sexual violence against women are interconnected, Adams aligns the butchering of animals with the objectification of women; vegetarianism with feminist equality. In their cannibalistic tendencies, the Maries ape the masculine stereotypes around eating to subversive and satirical ends. The girls overeat; they eat meaty, greasy foods; they eat messily and without manners: in subverting gendered expectations that exist in relation to eating and dining etiquette, the Maries mock – and ultimately disempower – the male presences in the film.

Visually dazzling and politically subversive, the Criterion Collection rightly celebrates Daisies as a landmark of feminist filmmaking. Over the six decades since its release, emerging feminist discourse around gendered bodily expectation and consumption have only served to heighten the film’s radicalism in the eyes of contemporary viewers.

Watching Daisies with my friend Alex over Skype one March evening in lockdown, I was hungry for the glossy Granny Smiths strewn across the checkerboard carpet in the Maries’ bedroom. Stomach rumbling, I felt myself fancying foods that I’d never tasted in real life, but were so vibrantly stylised on screen: a crisp glass of Cinzano followed by a mysterious skewer of pickled vegetables and a tomato stuffed with crab mayonnaise. When we’d finished watching, I skulked downstairs to the kitchen. I tried my best to reimagine the culinary explosion that I’d seen, but for lack of resources had to settle for the mundanity of a glass of orange juice and a cube of Cathedral City. So, for those who have yet to be mesmerised by the chaos of Daisies, be warned: make sure you have snacks to hand - and be creative with it.

Ashley Saville is an writer, art historian and plant mother based in East London.