There exists a relationship between le lieu de mémoire and French cinema, which provides some background on how cinema memory can be considered a part of cultural memory in contemporary art. It’s felt in no better place than the romantic visualisation of Paris in Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Amélie, which turns 20 this year. Aliya Arman explores how we must come to terms with our desire to return to a Paris which never was.

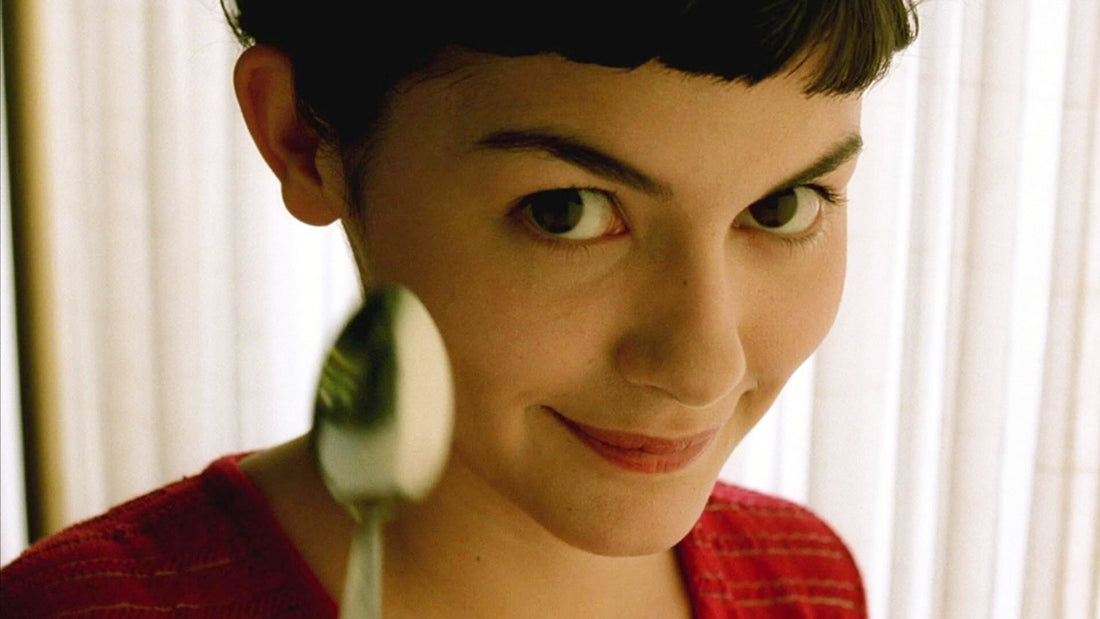

Plunging your hands into a bag of seeds; piercing the crunchy caramelised crust of crème brûlée with the tip of a spoon; skipping stones across the Saint-Martin canal – these are few of the small pleasures that make life worth living for the protagonist of Amélie.

2021 marks twenty years since the release of Le Fabuleux Destin d'Amélie Poulain starring Audrey Tatou as a wide-eyed café waitress in Paris, a candy-coloured romantic comedy which broke from the likes of Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s previous films Delicatessen (1991), The City of Lost Children (1995) and Alien: Resurrection (1997). As the new millennium dawns, the director’s cinematic fantasy turns away from the post-Freudian worlds he has created and towards a search for beauty in the banal.

In an interview with IndieWire, Jeunet explains how he knew the film would be a collection of individual stories, all tied back one way or another to the central story of a woman simply helping others to get by. He recalled: “We wanted to get a smile from the audience, so I knew I was going to talk about generosity and it’s a risk because today it is more fashionable to speak about violence”.

Leaving the world of realism and violence behind in favour of the surreal and generous set the tone of the film from the get-go. Before we even begin, the narrator discloses: “Amélie’s only refuge is the world she makes up.” Amélie may be wandering through the cobbled pathways of Montmartre in 1997, bearing little resemblance to the 18th arrondissement we know today, but it is the individual acts of kindness that make Jeunet’s fairy-tale endlessly spin like the Foire du Trône carousel. She carefully choreographs the perfect meet-cute between her hypochondriac colleague Georgette and resident cynic Joseph. She stands up to the bully grocer Collignon who relentlessly jabs at his meek but good-natured assistant Lucien. She even reunites a man with a rusty old box of forgotten childhood treasures, a moment which struck a chord so deeply for Bretodeau that he vowed to reconcile with his estranged daughter and the grandson he has never met.

The humanity and heart beating steadily through were what made Amélie such a hit. The film made nearly $174m worldwide to date, and eventually earned upwards of $33m in the US alone.

Then-French president Jacques Chirac and prime minister Lionel Jospin sung high praises for what later became the country’s most successful cinematic overseas export for over a decade, an understated feat for the subtitle-phobic English-speaking market. Chirac had even invited Jeunet for a private screening at the Palais de l’Elysée (which the filmmaker stylishly arrived to by bike as he snubbed the offer of a limo), curious to learn as to how a low-budget arthouse film about a Parisian boulevard do-gooder became an international sensation.

The film took the world by storm, to say the least. Except, not all were sold on the orange and green-hued dream of Amélie.

Serge Kaganski, editor of arts and culture magazine Les Inrockuptibles, didn’t hesitate to challenge the accolades, going so far as to claiming that if the French National Front were to ever need the perfect poster girl for a party-political broadcast, Jean-Marie Le Pen would need to look no further than Amélie Poulain. The film, he believed, was a sanitised form of cinétourisme, accusing Jeunet of showcasing a treacly snapshot of a whitewashed Paris that never existed.

In a now infamous review for Libération, he wrote, “Where are the Caribbeans, the north Africans, the Turks, the Chinese, the Pakistanis? Where are those who aren't heterosexual? Where are the Parisians who populated the capital in 1997?”

Kaganski did note that there was indeed one Arab character, played by French-Moroccan actor Jamel Debbouze, but he had effectively been deracinated with the traditional French name of Lucien.

However, portraying the sober realism of Paris – a city marked by both Princess Diana’s death in 1997 and the football World Cup victory in 1998 – was never the filmmaker’s intention. Jeunet famously opposed the earnest and often existential themes of the New Wave generation, and so saw his chance to use magical realism in a stand against the intellectual critics who “preferred the Cahiers du Cinema approach”.

“Cinema since the New Wave always seems to be about a couple fighting in the kitchen! I prefer to write positive stories,” the director said.

For Dr Isabel Vanderschelden, lecturer of contemporary French cinema at Manchester Metropolitan University, the world of Amélie exists in a certain temporal ambivalence, liberated from the realism of contemporary French cinema.

The film, she wrote in her book, is auteurist insofar as it began as a “small personal project” long cherished by Jeunet who was keen to incorporate surrealist-inspired elements that uplifted spirits, following the tragic news of the royal death which shook the capital to its core.

To bring the director’s fantastical Paris to life, the production crew cleared the cobbled streets of all cars, cleaned the graffiti off the walls of Boulevard de Clichy, and replaced the adverts at Abbesses métro station with expressionist aesthetics. The mixture of sepia and saturated hues in post-production – tones which work in digital colour and are not traditionally complementary in filmmaking – helped Jeunet “blur temporal markers and elide the boundaries between fantasy and the real”.

The jump between shots of the Gare du Nord and the Gare de l’Est, the melancholic accordion rhythms reminiscent of post-war Paris, and the gentle streets of Montmartre sans traffic jams and adverts, all gel together to form a semi-realist dreamscape based on bricolage and hybridity. The story of Amélie is one not frozen in a whitewashed past, nor alluding to a far-right vision. It’s one which draws on the surrealist elements to embellish observations of the ordinary at its heightened, and most saturated.

Reading between the lines was never imposed by Jeunet either. A scene which encapsulates the absence of greater meaning finds Amélie finally uncovering the identity of the man who has made multiple appearances in the scrapbook of discarded photobooth headshots: he is the photobooth repairman. Sometimes, meaning can be futile.

The clue was even in the title itself. Its original title in French Le Fabuleux Destin d'Amélie Poulain enchanted Francophone audiences with a rhyme fit for a fairy-tale, an omission sorely missed in the English translation. This was, after all, Amélie’s world, and we were searching for a cause through her crinkly eyes.

If anything, Mathieu Kassovitz’s role in a film that’s a world away from the Paris depicted in his own magnum opus La Haine strengthens the idea that this version of Paris was merely a painting, a deliberate deconstruction of the idea of film as a site of memory. Here, Kassovitz plays Nino Quincampoix, Amélie’s love interest who keeps to himself working as a part-time porn shop cashier, part-time ghost-train conductor. Paris is no longer home to the hyperconscious intellectuals as established by the New Wave. It is a city populated by les gens de peu like Nino, Amélie, Lucien, Dufayel and all the countless eccentrics of the everyday. We now notice the little guy struggling in a hostile world.

There is a pivotal moment when Amélie sits in a theatre, and she whispers closely to the camera with a sparkle in her eyes, “I like looking back at people’s faces in the dark.” The camera pans to a wider shot of the cinemagoers around her, all beaming at the big screen with a shared sense of wonder. Later in the scene, Amélie confides to us that she likes to notice the little details that no one else sees.

These everyday interactions, from the flight of steps that line the lawns of the Sacré-Cœur basilica to the busy metro Lamarck-Caulaincourt, reveal how we behave towards the people around us and in the spaces we occupy. Politics progress and regress. Buildings rise and fall. Jeunet teaches us how it is the details that are minute, fleeting and wonderfully bizarre, which humanise Paris, and a person.

For residents of the quartier today, the magic of Montmartre forever changed the mood of the neighbourhood. Two years after the original release, Laure Morandina, the head of Montmartre’s neighbourhood association, described the film as “a cloud of happiness on which everyone in the world would like to float”.

She added: “There are moments of the film that touched something universal and also captured the spirit of Montmartre as a village where even if the whole world visits us, we still know all the shopkeepers.”

Long after the two-week production stint, the shopkeepers were the ones who kept the façade going. Ali Mdoughy, real life owner of Maison Collignon épicurie, called the film life-changing, describing it as “a flame…and I don’t want it to go out.”

“I felt the place was losing its nostalgia, and the movie gave it a new breath,” he said. “It got people closer to each other. It’s quite magical, a happiness that invaded Montmartre.”

Of course, Amélie relies on cultural shorthand signifiers that may border on the saccharine at times. But for Jeunet, Paris was a canvas and he was her painter. Any attempt to search for realpolitik in a film that was acutely aware of how it was “modifying reality” ignores what is actually in front of us. We must accept that what we tend to overlook in ordinary observations is what Jeunet wants us to turn our attention to. That is where the magic truly lies.

Aliya Arman (@aliyadotcom) is a freelance journalist based in London. She loves films that make her cry, and likes to write on the intersection between race and class in fashion, culture and lifestyle.