Debut writer-director Prano Bailey-Bond takes us back to a time of great uncertainty in the UK with Censor – but her preoccupations with the material boundaries of reality and fiction, and the magic of filmmaking, go back much further than that. Savina Petkova explores the philosophies and mechanics of movies, and the control we give them, through Censor.

One of the paradoxes upon which cinema is built is the cohabitation of the desire for authenticity with the simultaneous repulsion of that very same reality represented, especially in death and horror. Censor, the title of Prano Bailey-Bond’s debut feature film, refers to its protagonist’s occupation. Enid (Niamh Algar) is a reputable film censor wrestling with lurking childhood trauma which creeps up through a compulsive mission, seeking to prove her long-lost sister is still alive and well. Professionally, all seems under control, since Enid’s job provides the solace of critical detachment when passing or banning horror flicks with the nation’s best interest at heart. That is until one day, when her penchant for control over images overlaps with the possibility of taking command of her own narrative. With that, the film criticises the then-dominant assumptions about the world as only either good or bad; completely real or completely fictitious.

The film takes place in 1980s Britain, when video nasties carved a contested space for themselves with the help of rental trade and straight-to-VHS release. On a practical level, the video player/recorder technology offered a sheltered, individual experience away from the prying eyes of moralist politicians, who in turn saw it as a condition that would enable people’s murderous intentions to unfurl. But aside from the unapologetic gore of video nasties, what troubled the government, and censors like Enid in Bailey-Bond’s film, has more to do with the perils of rewatching and disclosing the power of cinema’s concealed stillness.

In the early days of film theory and practice, if life was found in the motion of the pictures, death was associated with the still image only after the invention of cinema. A single frame was, consequently, nowhere to be found, disguised within the magic flow of film strips. It was not long after the advent of digital technologies, and more precisely home DVD players, that viewers could materialise the single frame as its own entity. In her 2006 book “Death 24 Times a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image” which deals with spectatoship and home video, feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey draws attention to a certain kind of pleasure that can be attained by using the pause and return function of video watching: the sensation of seeing “movement fossilised” and then reanimated. As any spectator unearths cinema’s knotty relationship to time and stillness when meddling with its flow, Enid’s job of carefully assessing films by pausing and rewinding, presents her with both the attraction and repulsion of image control in relation to death.

The idea that the single frame is ‘repressed’ when in projected – or digital – motion is fitting for Enid’s own susceptibility to claw at every material possibility that would disprove her sister’s death. A once suppressed childhood memory of the time she saw her sibling last, is vividly reawakened after a film watch: one by a banned filmmaker, which also features two sisters strolling in the woods at night, ending rather grimly. The correlation speaks to cinema’s potential to reawaken thoughts as what psychoanalyst pioneer Sigmund Freud terms ‘deferred action’. Concealed in a safe haven of one’s unconsciousness, a repressed memory still persists, as it is never completely edited out. Therefore, Enid’s traumatic memories underpinning the film’s unspooling can also resurface with the help of video controls.

Rearranging an animated stream of images – a film – via pause and repetition is, indeed, an act of control, and it clashes with a more traditional viewing condition. In a dark auditorium, with big screens and small seats, there is the following hierarchy: what’s shown is huge, untouchable, seducing the viewer to fully submit to the image’s hegemony. Precisely this setting led to the emergence of a paranoid-laden strand of film scholarship in the 1970s, the so-called apparatus theory. It goes like this: there are technological conditions in film projection which cement the viewer into a subjugated position. There is also this neurotic assumption that every film’s overarching morale could (and would) imprint itself onto the ever-vulnerable spectator. Apparatus theory provoked a wave of general distrust towards the medium’s power to ‘implant’ ideas as if straight to people’s unconscious in its analogue form, and this suspicion was only furthered by the advent of video technology in the particular case of UK’s video nasties.

The video revolution and the increased accessibility opened up the space for a more intimate (and in the logic of its critics, dangerous) kind of spectatorship. An example of that comes early on in Censor with a journalistic scoop linking a recent gory murder with a film that’s just been passed by the censor board, thus implicating Enid in moral negligence. While wondering how the so-called ‘Amnesiac Killer’ could not remember perpetrating the crime, the line that captures the paranoia of linking human behaviour with motion picture technology, is uttered by her coworker: “People construct stories to cope. You’d be surprised what the human brain can edit out when it can’t handle the truth.” Such an equation between film (editing) and the human brain suggests a specific kind of neuro-realism, which describes the boundaries between mind and screen as porous.

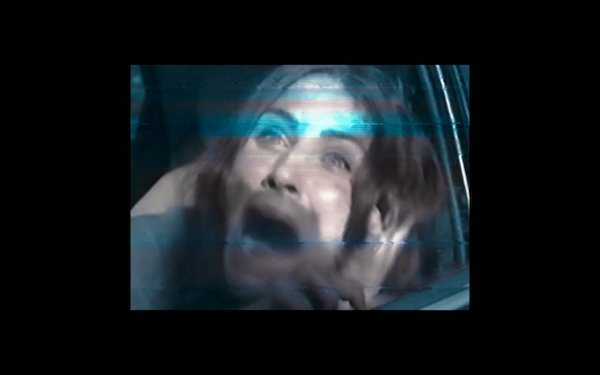

Ironically, the thing which proves decisive for Enid’s psychological state, is a sequence from a film she watches on video. Unknowingly, she enacts the government’s worst fear by letting a banned VHS affect her perception of reality. After borrowing an ‘under the counter’ title from a cautious rental store owner, Enid kneels down almost religiously in front of her TV. With her face inches away from the screen, the close encounter between two surfaces – body and screen – visualises the metaphoric parallel between them. Then, captivated by the doe-eyed redhead Alice Lee in a chiaroscuro-lit direct address, Enid presses the rewind button. This causes the image of Alice to become compressed and distorted, sliced by lines of static. It is the act of rewatching that convinces Enid the actress is her lost sister, and such confirmation would not be possible without the power of manual intervention. Manipulating the image, rearranging the flow of time, and bringing a still frame out of its context grants Enid some short-lived control over her own narrative.

It’s not only the narrative’s crucial points that mark the protagonist’s manic descent: the film’s spectacular and lurid visuals cast an ambivalent veil over Enid’s own perception of reality. A luscious production design by Paulina Rzeszowska forms a smoky, labyrinthian set of both house interiors and unexplored forests which feel equally foreign, emulating the atmosphere of the video nasties to a mise-en-abyme effect. In addition, the film’s cinematographer Annika Summerson shot on 35mm film stock to ensure the film’s texture matches its conceptual underpinnings. Censor also reconfigures its aspect ratio numerous times, both at its beginning and at its end. In both instances, the ratio shrinks from wide (2.39 : 1) to full frame (1.33 : 1), to wide and full frame again, mirroring Enid’s own shifting perception of reality, and challenging the viewer’s own perspective at the same time.We, the audience of someone else’s viewing , realise we’ve been sharing another gaze only after it’s been taken away from us.

In the film’s opening sequence we see a woman’s body, painted red; flaming red is also the colour of her silhouette with its sharp outlines amidst a forest’s night of smoky darkness. The sequence lingers hauntingly as a glowing daze of grain, vermillion and purple tangles into an unstable image of a young woman being dragged out of sight. Amidst the echo of her deafening screams, a crackling sound freezes the attack in its tracks, pausing. And while static flickers at the squared edges of the paused image, it seems that the nameless woman is somehow resisting the standstill of her gruesome fate. In comparison, the film’s final scenes follow a frantically violent episode with a rose-tinted dream. A fantasy of rainbows, soft contours, and long-lasting smiles is soon cut open by the insertion of very distinctive still images, which disrupt the sequence flow.

Amidst the soft-focus smoothness and the scene’s illuminating warmth, Enid daydreams about taking her sister home, straight to her parents’ loving embrace but twice the frame trembles, and the mellow hues are suddenly swapped with ice-blue versions of what seems a nightmarish alternative reality. In the dream, Alice is dozing off with a smile, her head peacefully leaning on the passenger seat door, and in the blue nightmare, the same close-up shows the young woman screaming hysterically. By inserting the green-blue, glitchy image of fear, editor Mark Towns (who also did a marvellous job for Rose Glass’s frenzied horror Saint Maud in 2019), visualises the battle of film surfaces and the deferred action of images once repressed. For the blink of an eye, the gruesome nature of reality – suggesting that Enid has kidnapped a stranger – slices through the shiny veneer of the daydream.

Precisely because these revealing moments last for such a short time, the only way to engage with them attentively would be to rewind and pause ourselves. When people eventually interact with Censor at home, they could, potentially, pause and play, rewind, fast-forward, count the ratio shift, examine the glitchy inserts of what seems like another film covered by the film itself. The viewer could even follow Enid in her undoing – borrow her gaze, and re-enact her steps, if and only if they dare take part in something presumably ‘nasty’.

Savina Petkova (@savinapetkova) is a film critic/PhD candidate based in London who lives from one film festival to another. She specialises in animal representations in contemporary film and writes for Electric Ghost Magazine and MUBI Notebook.

Shop our Prano Bailey-Bond & Niamh Algar t-shirts.