Black femininity was always considered a hard sell in Hollywood, but Hattie McDaniels and Dorothy became the perfect women to peddle racist stereotypes – despite both having, as history has shown, so much more to offer. Lynda Cowell looks back at the two tropes that defined two stars.

I first met Hattie McDaniel through our mutual friends, Tom and Jerry. I didn’t know her name but I knew that she was shy. On screen, she insisted on only revealing herself from the calves down, but that didn’t matter – I knew a formidable presence when I heard one.

For a while, the penny failed to drop. When I saw Gone With the Wind for the first time it didn’t immediately connect that the harassed footsteps of Tom and Jerry’s maid was supposed to be McDaniel’s cartoon incarnation.

Mammy, cartoon or otherwise, was a character that had been a part of America’s collective imagination for a while. After appearing in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 book, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, mammy started to get around. Despite the fact that slaves were given very little to eat and were often worked into early graves, the notion of the large, middle-aged, dark-skinned Black woman who loved her owners more than life itself, became cherished. And why wouldn’t it? With no husband, children or family to ever speak of, this loyal, motherly, sexless husk of a human being posed little threat to white society. It was McDaniel’s portrayal of mammy that came to embody a character that still sets the standard for Black actresses today.

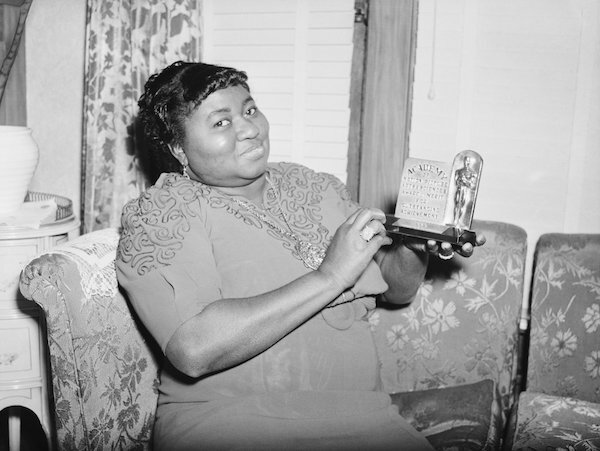

For McDaniel, the role turned out to be bittersweet. On the one hand, it earned her the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress – the first for any Black actor – but on the other, she was heavily criticised for taking the role at all. The National Association for the Advancement for Coloured Peoples (NAACP) hated her lip-puckering, eye-rolling antics and accused her of degrading her race. In response, she explained that the role had given her the chance to improve working environments for other Black actors as well as herself. When it came down to it, she said: “I’d rather get paid $700 a week playing a maid than $7 working as one.”

In stark contrast, Dorothy Dandridge was everything McDaniel wasn’t: light-skinned, beautiful and petite, she was 5ft 4 inches worth of exoticised trouble. Any sexuality that had been removed from mammy at birth had seemingly been transplanted into Dandridge’s often hypersexualised frame.

As a kid, it was easy to spot the difference: mammy was just a funny Black woman who provided the light relief in a three-hour long film, but Dandridge was different. I could see that she was the kind of light-skinned lovely every young Black girl should aspire to be, but like most things to do with racism, there was a lot more to it. And it was down to me to discover it.

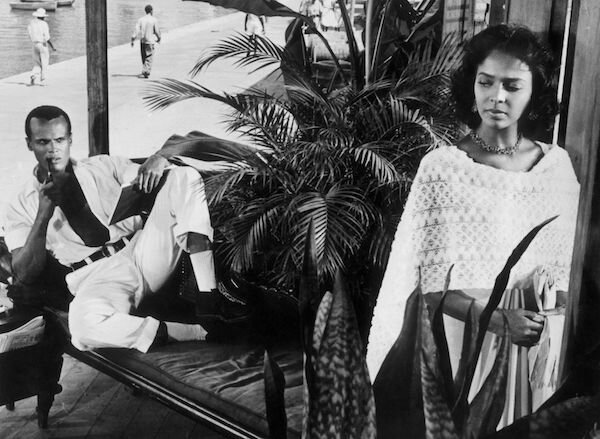

The more I read about the two women, the more I recognised their commonalities. McDaniel and Dandridge might have looked worlds apart but they both suffered the same fate of being trapped by their race; something neither beauty nor talent could override. For every loyal domestic that McDaniel played, Dandridge matched her in roles that heightened her exoticism, sensuality and danger. From Carmen Jones and Island in the Sun to Porgy and Bess, Dandridge’s roles were always going to be limited and she knew it. In Carmen Jones, the all-Black remake of the Bizet opera Carmen, she plays the tricksy, man-luring parachute maker who men instantly fall in love with and in Porgy and Bess, Dandridge is the sultry temptress, Bess who is irresistible to men. When the roles started drying up she pretty much gave up trying. Dandridge died of an overdose at the age of 42.

Although McDaniel and Dandridge’s lives have been revisited over the years, both have shared the limelight again recently. Not only did McDaniel’s legacy become a talking point again when Black Lives Matter protests prompted HBO Max to stop streaming Gone With the Wind, she also cropped up in Ryan Murphy’s Netflix miniseries, Hollywood. Played by Queen Latifah, some of McDaniel’s heartache is highlighted by the contrasting success of her friend in the show, Camille Washington – a character clearly based on Dorothy Dandridge.

The series has merit, if only to register how truly fantastical it is. Based on real and fictitious people, it follows the lives, loves and careers of a group of wannabes in post-WWII Los Angeles. Laura Harrier plays Camille Washington, a Black starlet whose beauty, white scriptwriter boyfriend and sheer pluck lands her the lead role in a major movie. The whole thing stinks of idealistic fairytales.

It’s easy to see what Murphy, the show’s co-creator and executive producer, was trying to do. By having Black leading ladies, interracial romances, openly gay heartthrobs and Black scriptwriters, he aims to reimagine the world in what-ifs. But in the process, Murphy erases actual historical realities that many people are still unaware of.

On YouTube, there is footage of Hattie McDaniel collecting her award at the 1940 Oscars ceremony. Naturally in black and white, it’s hard to tell that her dress is vivid blue and her flowers are white, but it’s also hard to tell how racism has affected her evening. The hotel’s strict ‘no Blacks’ policy meant that her seat was so far from the stage, and from her co-stars, that she was practically outside. It’s an indignity which carries on into the night, when the afterparty – held at a ‘no Blacks’ nightclub – forces McDaniel to find an alternative place to celebrate her historic win.

Segregation loomed as large on screen as it did in real life. In 1930, Hollywood studios were presented with the Hays code, a long list of do’s and don’ts for making movies. It outlined the set of rules that films should abide by if they didn’t want to be banned, censored or canned completely – one of which forbid any kind of onscreen romance between Black people and white people. This rule even extended to films such as Pinky, a 1946 drama about a light-skinned Black woman who ‘passes’ for white. Although Dandridge was considered for the lead, the studio couldn’t take the risk of provoking a backlash with an interracial romance.

But while many would argue that things have completely changed, you don’t have to scratch too much of the surface to see that roles for Black women are still limited.

Fifty years after McDaniel won her award, Whoopi Goldberg received the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress, for her role in the 1991 film Ghost. Her character, Oda Mae Brown, isn’t a domestic but she is antsy and comical, matriarchal and indispensable to the white characters in ways that aren’t too dissimilar to McDaniel’s characters before her.

In 2001, Halle Berry became the first “woman of colour” to win the top prize of Best Actress, for her role in Monster’s Ball. Again, the stereotype isn’t immediately obvious but Berry is small, light-skinned, and enough of a temptress to lure a racist prison guard into her bed. Berry is so much in the mould of Dandridge that she played her in the 1999 biopic of her life, Introducing Dorothy Dandridge.

It’s not much of a revelation to declare that all actresses have it tough in Tinseltown. In a place where 35 years old is considered ancient, I’ve always been surprised by Hollywood’s eagerness to swap sexual allure for a ‘mumsy’ glow. But for Black actresses the struggle is harder still, especially when the options are still limited to two stereotypes.

The most damning proof of all this is the Oscars itself – you only have to look at the list of Black women who have been Oscar nominees and winners since Monster’s Ball. Between 2001 and 2018, 15 Black women were nominated for Best Supporting Actress, and only six won. The films ranged from Precious, telling the story of a dark-skinned, overweight Black teenager to The Help, a film about Black domestics during the Civil Rights movement in 1963, and Harriet, a biopic about the abolitionist and political activist born into slavery, and 12 Years a Slave. None of the five Black women nominated for Best Actress across these films won.

It’s true that some of these films were written and directed by Black people, but it’s clear that the predominantly white Academy who choose the winners only really want to see certain portrayals – and that’s a problem. The hope, if there is any, is that only Hollywood can rectify all this. When the movie making industry becomes more diverse then we might see more complex portrayals of Black women on screen. But until then? Mammy and the femme fatale are going nowhere.

Lynda Cowell has written for The Voice newspaper, The Guardian and Time Out, amongst others and had a long stint at the BBC as a television researcher. Studying film at university many moons ago could have spoiled her enjoyment of cinema, but fortunately it didn’t.