In her play Le Vertige Marilyn, Isabelle Adjani embodies Marilyn Monroe to explore the complexities of stardom, historical identity, and legacy. Olympia Kiriakou unpacks the star-making task at a time where there are more images of Monroe than ever.

On 17 May, 2022 the Elle France Instagram account teased a mysterious blonde woman whose face was covered by a baby pink chiffon scarf. For many, it was easy to guess that their latest cover girl was Isabelle Adjani. A few weeks earlier, the five-time César award winner had announced that she was adding more dates to her one-woman show, Le Vertige Marilyn, which writer Olivier Steiner adapted from a series of interviews given by Marilyn Monroe to reporter Richard Meryman weeks before her death on 4 August 1962. In the show, Adjani borrows elements from Monroe’s appearance and life story to perform a series of intimate monologues about fame, identity, and self-reflection. Her transformation interrogates Monroe’s mythology, which today straddles the line between actress and exploited pop culture motif. Crucially, too, Adjani’s multi-layered performance underscores the liminality of film stardom and the complicated terrain of star-as-cultural iconography.

Adjani’s fascination with Monroe grew from a series of “mystical” connections over the course of her 52 year career. In her Elle interview, she reveals that while filming Tout feu, tout flamme in 1982 with Monroe’s Let’s Make Love co-star, Yves Montand, he confessed that she reminded him of the late actress. Years later during a photoshoot for Egoïste magazine in the early 1990s, Richard Avedon placed a shearling coat that belonged to Monroe on her shoulders. Adjani recalls that moment as being a “skin to skin" meeting, a description that invokes an intimate bond between the two women. Monroe’s tumultuous childhood is also deeply personal for Adjani. She is notoriously tight-lipped about her private life but has spoken candidly about her early years, and in Le Vertige Marilyn she describes her parents as “two opposing currents that cross each other.” Adjani’s distant relationship with her mother, who viewed her as a “feminine rival,” propelled her natural affinity for stars like Monroe because “… childhood trauma creates a deep desire, a vital need to be someone else…That's what I did, that's what Norma Jeane did by creating Marilyn Monroe.” Their respective professional metamorphoses get to the heart of the liminal nature of stardom: donning the mask of fame and “creating” another being via performance allows actors to escape into multiple identities, almost like a second skin.

In Le Vertige Marilyn, Adjani draws upon her own vulnerability to explore that of her subject. The minimalist set design, delicate haunting music, and dim lighting package by Emmanuel Lagarrigue add a dreamy quality to her performance, as if she’s inhabiting an otherworldly space. At one point Adjani reflects on Monroe's death, saying, “…a star is about to go out, the whole world wanted to hold her…the whole world isn’t there,” alluding to the paradoxical loneliness that can accompany fame. Her cadence is hypnotic; she speaks in a breathy tone typical of her acting style and that of Monroe’s own performative voice, and their vocal similarities are magnified when paired with audio clips from Monroe's unfinished film from 1962, Something’s Got to Give. In a further nod to the duality of Adjani’s performance, her hair remains its signature dark shade with bangs. On the eve of the show’s July premiere, she took to Instagram to write, “Yes, [my] hair is jet black but platinum is not far away, under the waves…” Throughout, she acts as a version of herself and someone else.

Adjani has not shied away from playing historical figures, as is evident by her turns at Adèle Hugo in L'Histoire d'Adèle H. (1975), the titular character in Camille Claudel (1988), and Diane de Poitiers in the upcoming TV movie Diane de Poitiers: La Plus Que Reine. However, the cultural ubiquity of Monroe’s blonde bombshell image and the rocky terrain of her posthumous legacy add a unique wrinkle to Adjani’s latest characterisation. The commodification of Monroe’s persona in the years since her death has transformed her into a pop culture figure representing more than just herself. Her stardom is grounded in classical Hollywood but, like other movie stars, her image was also a universal touchpoint in wider discussions about societal values, mores, and history. Richard Dyer notes that at the peak of Monroe’s career, her name “virtually became a household word for sex,” and her hyper-feminine image personified evolving ideas about sex, gender, and women’s roles in the mid-twentieth century.

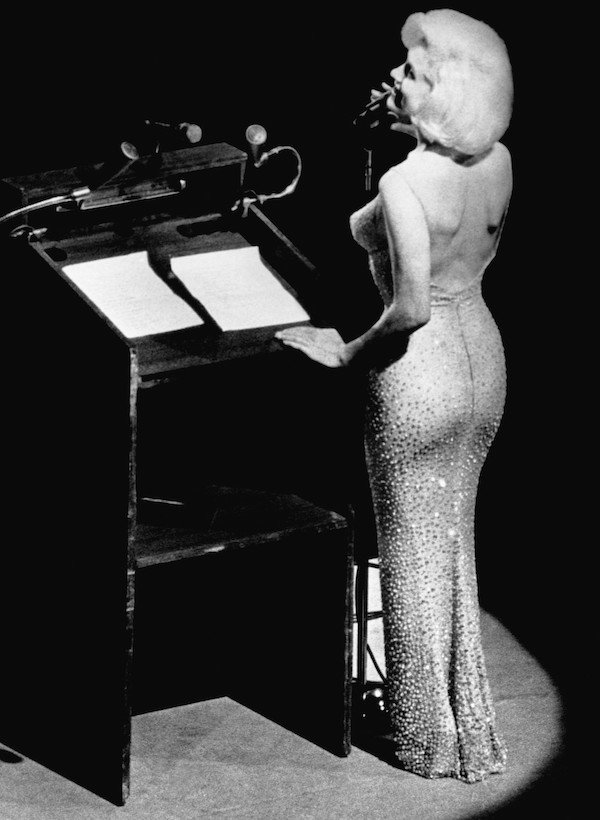

Monroe’s stardom was moulded by the Hollywood studio system, but her agency in her own star-making process cannot be ignored. By all accounts Monroe was intellectual, well-read, and devoted to her craft, and she also understood the role of her “dumb blonde” persona in the cultural climate of the 1950s. According to her friend Lucille Ryman, she was “tough and shrewd and calculated” when it came to her career decisions. In spite of Monroe’s desire to be taken seriously as an actress, the exploitation of her image often overshadows her methodology, rich body of film work, and complicated star persona. Her posthumous iconicity can be summarised into identifiable signifiers: platinum blonde hair, a white dress, and plump ruby red lips. Collectively, they are the foundation upon which countless media portrayals, parodies, merchandise opportunities, and even theme park characters are based. Few movie stars have transgressed their unique historical moment in quite the same way, but at the same time, few are as misunderstood. We are left with multiple Marilyn Monroes: cultural icon, exploited victim, and self-creator. But perhaps, like most stars, she actually exists somewhere in between all of those identities.

For those reasons, becoming Marilyn Monroe is a fraught endeavour. There are rare moments when Adjani ventures into the murky waters of presumed familiarity that often frames star discourse. For example, she claims she “instinctively” knows that Monroe would approve of the sustainable Courbet jewellery she wears for the Elle cover shoot. Adjani does not know her subject intimately to speak as her authoritative voice, but she also emphatically rejects the notion that she’s merely impersonating Monroe. Instead, she borrows elements from Monroe’s persona to approximate her aura and, as the play’s title suggests, interrogate her intoxicating charm. When asked by Elle why she was “posing" as the late-star, she jokes, “Oh dear! I'm not posing as Marilyn Monroe, it's Madonna or Kim Kardashian posing, right?” There’s an empathetic quality that threads together Adjani’s performances, and she admits that she is drawn to stories about women who have been “overlooked” by history such as the aforementioned 19th century sculptor, Camille Claudel, or Margaret de Valois in 1994’s La Reine Margot. Adjani explains that she loves to “rebuild the memory” of her heroines, and by embodying their spirit she attempts to “correct” their warped historical narratives. Marilyn Monroe is anything but an unknown figure, but her caricaturization in popular culture makes her an overlooked heroine in a different sense. Adjani’s homage largely succeeds because she acknowledges the mythology while centering her performance on the effects of stardom on Monroe’s emotional complexity and humanity.

Marilyn Monroe is once again at the forefront of our collective consciousness with Blonde. Discussions have already arisen about the film’s exploitative spin on her life, largely based on its fictional source material and director Andrew Dominik’s statement that it has “something in it to offend everybody.” Marilyn Monroe tributes proliferate our cultural landscape, but Isabelle Adjani’s performance offers a unique take on the late star. For as much as she pays homage to Monroe, her transformation is actually a meditation on stardom itself. Through Marilyn Monroe, Isabelle Adjani explores the liminal space that exists between a star’s image and their tangled cultural identity.