READ ME is a platform for female-led writing on film hosted by Girls on Tops. Louisa Maycock (@louisamaycock) is Commissioning Editor and Ella Kemp (@efekemp) is Contributing Editor.

On 21 November 2018, Twilight is 10 years old. To commemorate the anniversary of Catherine Hardwicke's divisive relic, former Twihard Katie Goh reckons with the complicated history of its fanbase and the misogynistic hand she was dealt.

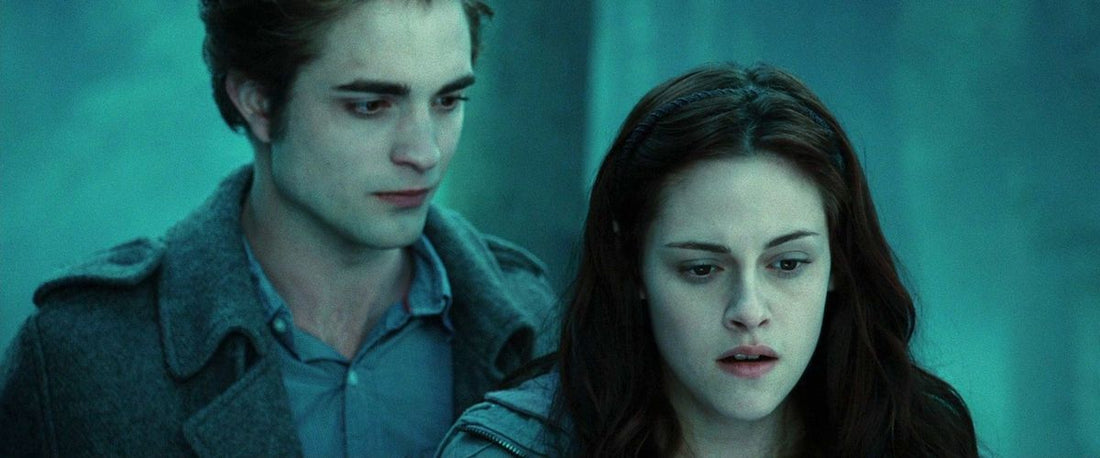

Ten years ago, a movie franchise was born that sucked the life out of teenage girls, a cultural phenomenon that bordered on hysteria. Or rather, that’s the narrative critics of Twilight would have you believe. In reality, ten years ago, a fantasy coming-of-age movie with the aesthetics of an indie was released. Directed by Catherine Hardwicke and made on a small $37 million budget, Twilight was your basic girl-meets-boy-then-boy-turns-out-to-be-a-vampire story, starring Kristen Stewart and Robert Pattinson. At its essence, Twilight, and its three sequels (though not directed by Harwicke) are about a young woman becoming sexual for the first time while some vampires and werewolves fight around her. What could be the harm in that?

Turns out the harm was the fans. On its opening weekend, Twilight made $70 million at the box office, nearly double its budget. Worldwide it made $403 million. In 2008, the film’s commercial success was a record for a female director (ironically, Hardwicke’s record was beaten in 2014 by Fifty Shades of Grey, a movie based on E.L James’ novel of the same name that started its life as Twilight fanfiction). Summit, Twilight’s studio, hadn’t expected it to succeed despite Hardwicke’s conviction that the books already had a small but powerful fanbase. During the shoot, the director was kept reigned in on a tight budget and repeatedly told by studio executives that “girls don’t see movies”.

While it seems unimaginable now to think of Hollywood not marketing towards women, ten years ago Twilight was breaking new ground. Before Twilight, young adult franchises were aimed towards a male audience – Harry Potter, Spiderman, X-Men, Pirates of the Caribbean, The Dark Knight trilogy, and Transformers to name a few. While there was an awareness that these movies had female fans, they were largely ignored in favour of the larger, generally male, audience. Twilight was different because it was a movie about a teenage girl for teenage girls, and when 80% of Twilight’s audience ended up being female, Hollywood producers sat up straight. Suddenly young women at the box office were important. After Twilight came the film franchises, The Hunger Games and Divergent, and the television shows, The Vampire Diaries and True Blood. Even superhero movies like Wonder Woman and the soon-to-be-released Captain Marvel can be traced back to Twilight’s financial success, the moment when Hollywood realised that – surprise! – women want to see movies about women.

And so, a fandom was born. While female fan groups were nothing new in music (hello Beatlemania), a massive, predominately female movie fandom hadn’t been seen before in cinematic history. It was the first time fans were using the internet on a mass scale to connect with one another. These were the days when social media platforms and forums were just beginning to gain popularity, and Twilight fans hungrily sunk their teeth into them. Twilight was the first movie Twitter account to reach one million followers, and this was the first time fans used hashtags to show their loyalty— #TeamEdward or #TeamJacob (shoutout my #TeamEdward gang). On YouTube, fans were emotionally gushing about what the franchise meant to them while on Tumblr, dedicated fan blogs multiplied like dividing cells. WattPad, FanFiction.net, and Live Journal filled up with fans’ creative stories about their heroes. After Harry Potter, Twilight is still the second most popular franchise on FanFiction.net.

Importantly, Twilight’s online fan presence allowed anonymity. While Twilight is one of the most popular franchises to have existed, it’s also the most despised. Female fans were labelled “hysterical,” “crazy,” and “obsessive” by the media, assigned gendered language which would never be applied to Star Wars or Batman fanboys. Twilight and its fans were the target of thinly veiled misogyny, often by middle-aged men who couldn’t understand that they were not the film’s intended audience. In a Time Out article titled “Twilight Sucks”, Hank Sartin described how fans were being “duped” by the franchise’s “brilliant PR campaign”. God forbid, young women have any agency over what they love. Meanwhile, old school horror fans were aghast to find that the archetypal blood-sucking monster of the genre was now a vegetarian(these vampires only feasted on animal blood, never human), sparkling heartthrob. Here, the supernatural man was sexualised, rather than the woman he prayed on.

Even within the supposedly safe sanctorum of fan culture — Comic-Con — Twilight was derided. During peak Twi-mania, the reception to the franchise was openly hostile. When Twilight and its sequels became annual visitors to Hall H’s sacred walls, a number of Comic-Con regulars became angry that Twilight fans were taking over. “Twilight ruined Comic-Con” became a war cry for regular attendees. In a 2015 HitFix YouTube video, a man in a Deadpool costume explains just how the franchise ruined the convention. “Twilight messed up a lot of things out here for Comic Con”, he says. “Now you got the teeny-boppers out here waiting in line for days just to get ticket”.

Unlike Comic-Con’s biggest fandoms – Marvel, DC, Star Wars – Twilight devotees are predominately young and female. Haters may as well have said that teenage girls ruined Comic-Con. In a 2009 Live Journal blog (also) titled “Twilight Sucks”, one blogger describes being dragged to the New Moon panel by his Twihard younger sister and seeing a protest of “Twilight Ruined Comic-Con” signs outside the hall. “It was great seeing all the people passing by cheering them on and giving them high-fives”, he writes.

Whether for better or worse, Twilight and its fan presence changed the fan convention. While Comic Con became more mainstream and commercial, it also became more accessible to new genres and audiences. Twilight opened the Comic-Con door for more female-centric fandoms, such as Glee and The Hunger Games. Even The Good Place’s Comic Con panel in 2018 can be attributed to Twilight opening the doors.

Writing this feature and looking back at Twilight’s reception has been bittersweet. As a teenage Twihard, I loved the first film, and, like many of its fans, experienced the ridicule and misogyny aimed towards the franchise. My time in the Twilight fandom was short, but it had a lasting impact. Watching Twilight made me commit to vampire lore which made me commit to the horror genre which made me commit to film history which made me become a film writer.

Rewatching Twilight ten years after its release has been cathartic. While its gender politics remain undoubtedly questionable, there’s still much to enjoy; from Kristen Stewart’s breakout role as a lip-biting nerd and Hardwicke’s indie roots being channeled into a fantasy world, to the noughties fashion with matching emo soundtrack (let us never forget that iconic baseball scene played out to Muse’s ‘Supermassive Black Hole’). Revisiting a foundational moment in my teenage years, one that I was made to feel embarrassed about, has been therapeutic. When the franchise’s last film, Breaking Dawn Part 2 was released in 2012, I had long since abandoned my Twihard days and was part of the mob that mocked the franchise and its fans. I had internalised the misogyny I’d once experienced. So, happy tenth birthday, Twilight. I’m sorry you were treated so badly. I’m sorry to the lanky, teenage girl who loved Twilight, and was made to feel ashamed of that love too.

Katie Goh (@johnnys_panic) is a freelance arts writer and editor based in Edinburgh. Her words have popped up in The Guardian, Sight and Sound, Dazed, The Independent, The Skinny, Huck, and more.