In Henry Selick’s Coraline, the titular character enters the Other World, an alternate realm that appears perfect on its surface, but is ultimately revealed to be a dangerous nightmare. But, for the Black ghost girl, the Other World was likely a solace from anti-Blackness – Kassia Neckles dives in to explore the post-racial potential of this fantasy.

Coraline first happens upon the Other World after opening a small door she discovers in the apartment her family has just moved into. The Other World is Coraline’s reality, but copy-and-pasted and then elevated: her rainy Portland environs are replaced by a sleekly perpetual nighttime, the muddy and un-tiled garden is substituted by colourful flowers planted in the shape of her face, her dinners of overcooked chard and mystery casserole are swapped for roast chicken, mango milkshake, and cakes that read “Welcome Home.” Most notably, however, is that unlike in the real world, where her parents are inattentive workaholics, her parents in The Other World are fun and loving and present. And they look exactly like her real parents, save their eyes.

Coraline initially falls for the fantasy, but it gradually unravels, initiated by the Other Mother’s morbid request: that she have buttons sewn into her eyes so that she can remain in The Other World forever. The Other Mother presents her with an array of options for colours — pink, vermillion, chartreuse. However, she admits that “Black is traditional.”

For me, it is in this three-word affirmation that the Other World’s post-racial potentiality first emerges. While the Other Mother is explicitly referring to buttons, what could a phrase like this connote to Coraline if she were Black and she had entered the Other World as an escape from anti-Blackness? This question is substantiated by the discovery that not only is Coraline not the first person to venture into the Other World, but that one of her predecessors was, in fact, a Black girl.

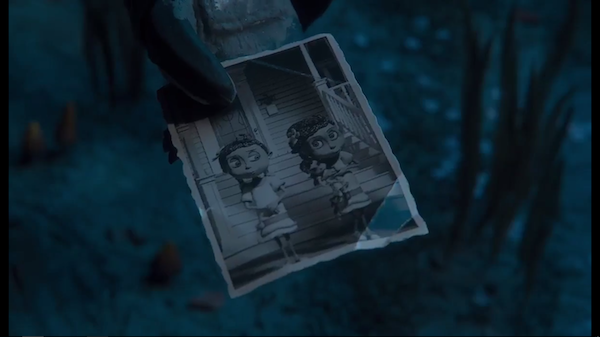

Coraline meets this girl at the film’s climax. She is one of three children who had actually taken up the Other Mother’s offer to have buttons sewn into their eyes, only to have her soul held hostage, and be left to waste away in confinement. While the Black ghost girl, who remains nameless for the entire film, is seemingly only a minor character, her existence and ultimate demise reshapes the way The Other World can be understood.

Coraline’s life might be boring and tedious, but it’s good — her parents are successful at their job, she has food to eat and a roof over her head, she has a potential friend in Wybie, and, above all, she is safe. In this sense, Coraline can reject the vision that the Other World proposes because it is only superficially better than the actual life she leads. This is why she is able to take the unprecedented route of refusal — the life that she has waiting for her outside of this Other World is liveable.

I imagine this was not the case for the Black ghost girl. It is unclear exactly when she was stolen by the Other Mother, but we can hypothesize that it was many decades ago. In the original book by Neil Gaiman, it is said that her sister went missing in 1952 — if we are to examine Coraline as taking place in the same year that it was released, that was 57 years ago.

While anti-Blackness is undeniably still alive and well, 1952 for a young Black girl in the United States would have been a volatile, dangerous time, with Jim Crow having yet to be abolished, and with her existence fettered by anti-Blackness the likes of which we are unable to fully conceptualize now. The Other World, for this little girl, might have been more than simply a world where her parents seem to care a little more and the food is a little better – it was likely a space that promised a post-racial reality.

There is an undeniable qualitative difference between a world where the flowers in the garden are inanimate, a gravy train travels around the table at dinner, and a circus of mice is always performance ready downstairs versus a world where an individual can hope to navigate the world without worrying about falling victim to constant, systemic racialized violence.

The loss of the Black ghost girl is a tragedy. The exact age that she was at the time of her disappearance is never confirmed, but she was definitely very young. Additionally, the reason for her disappearance was unknown for all of these decades, thus leaving a mourning and confused family behind. The Black ghost girl is heavily implied, and ultimately confirmed, to be the missing sister of Wybie’s grandmother who owns the apartment complex that Coraline’s family has just moved into, and it is the loss of her sister that has made the grandmother wary of ever allowing families with children to move into the complex. Coraline might be the first child to ever grace the complex since the sister’s disappearance via the Other World.

However, I find that the particularly tragic aspect of the Black ghost girl’s demise (beyond the actual action of having her eyes replaced with buttons, her soul stolen, and her body left to waste away) to be the degree of sorrow she faced in the real world, and the consequential false hope she faced in the fake one. This was not a girl who wanted to escape her life because of its dullness, but who needed to escape because it was volatile. And whereas Coraline could always find something to do to alleviate this boredom, there is nothing the little Black girl could do to alleviate her racial subjugation. So desperate was this girl to exist in a world where she could be safe from oppression, that she was willing to give up her soul for it.

This consideration significantly recontextualizes the allure of the Other World. Even when Coraline is enjoying herself there, she can still tell that something is slightly off — the lights shine a little too bright, everybody smiles a little to largely, the moon glistens ominously. I doubt that the Black little ghost girl wasn’t wary of the Other World, or didn’t notice these clues. But the Other World likely still trumped the danger of her reality. A fake world where one does not have to live with the spectre of anti-Blackness is infinitely better than a real world, where one has no choice but to.

I imagine the little Black ghost girl, sitting at the dinner table like Coraline, as the Other Mother proposed the replacement of her eyes. “Black is traditional,” she would have said at the end of her spiel. Of course, at least literally, she was talking about the buttons that would be sewn into her face. But I imagine, too, that this meant something different for the little girl. Perhaps, instead of an omen of horror, she saw this as a call home.

Kassia Neckles is a film and English student and writer based in Toronto. She is passionate about Black cinema, loves a good chick flick, and wishes life were more like a musical.

.png)