For centuries, Black people have been forced to assimilate in a Eurocentric society – one that, particularly for women, has demanded a certain beauty standard that favours straight hair. Revisiting Agnès Varda’s Black Panthers and The Black Power Mixtape 1967 – 1975, Maya Campbell explores how hair is a sacred means of expression and a symbol of liberation.

It is only in the last few years that I have come to understand the secrets of my hair. How to nurture my wild curls and tresses, but most importantly, to not wish it was anything other than what it is. Growing up with Nepali relatives, a mother and grandmother who had straight, long hair, meant I sometimes wished mine was longer, easier and less troublesome. As a young girl I envied the ease with which their hair flowed down their backs, smoothed into a ponytail, not requiring large portions of time to comb and oil before sleeping, and in the mornings before school. Luckily, my grandmother and mother always encouraged me to keep my hair natural, and educated me about the harms of using heating tools to straighten curly hair, as they sensed the longing within me before I had uttered it aloud. It was during a trip to see my Jamaican father that my hair went through a painful, yet transformative experience: my step-mother convinced me that I would look prettier and more girlish with straightened hair – like her. Afterwards, my hair was so broken and ravaged from the process that I had to chop it all off when I went home, a traumatic experience for an eight-year-old girl who at the time thought long hair was the epitome of female beauty. To this day, I use only natural hair products – almond oil, olive oil, jasmine oil – and have never set foot in a hairdressers. Over time, it has become a ritual, a treasure that I guard resiliently.

Hair occupies a sacred position in African culture; our hair requires time, knowledge and care to embody its full potential. During the Atlantic slave trade, lasting from the 16th to the 19th centuries, the dehumanising living and working conditions did not allow for any kind of hair care. The deportation of millions of Africans isolated them from traditional practices and, in many cases, their hair was forcefully shaved to strip them of any remaining cultural identity. Even after emancipation, the severe reverberations of 400 years of historical bondage distorted all areas of life for Black people, and culminated in a collective rejection of letting their hair grow out as biology intended. Natural hair was seen as unruly and dirty by white employers and business owners, and acted as a barrier to gaining employment in the Western world. In order to further assimilate into white society, many Black men and women sought out harmful processes to turn tightly spiralled curls into straight hair, concealing the physical feature that distinguishes us from other racial groups.

One of these inventions was the hot comb, patented by Madame C.J Walker during the Reconstruction Era (1865-1877). In domestic settings, it was heated up to 65 degrees Celsius, leaving behind scalp burns and enforcing a regime of self-hatred. Walker was said to have desperately prayed to cure her appearance, and the many tonics and hot combs she produced as part of her lucrative business were marketed at promoting ‘healthy’ hair – a synonym for ‘straight’ – despite the steep personal cost. The notion of ‘taming’ a Black woman’s hair is deeply embedded in the Eurocentric framework of beauty – 50 of hair products targeted towards Black women contain chemicals linked to cancer, infertility and obesity. Another popular method includes using relaxers, a type of lotion that makes curly hair easier to straighten. Many contain hormone chemicals, parabens and phthalates. Parabens have been linked to breast cancer, due to their ability to mimic oestrogen and therefore trigger increases in breast cell division and tumour growth. Several phthalates used in this chemical process have been linked to asthma, neurodevelopmental issues, breast cancer and many more diseases in studies conducted over the past five years.

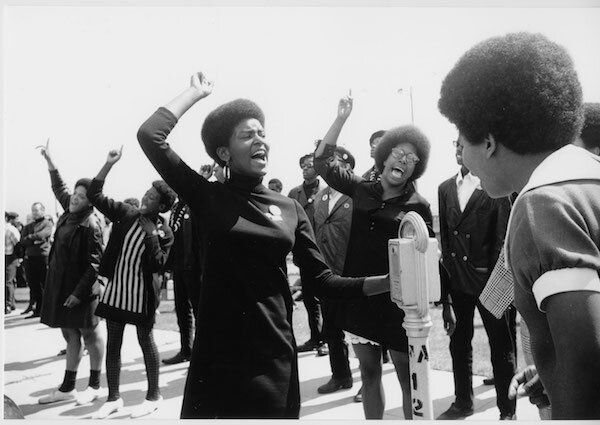

The Civil Rights movement, lasting from the early 1940s to the late 1960s, also birthed the Natural Hair Movement, which saw the spherical style of the Afro come to represent the spirit of the revolution. The Black Panther women and musical activists, such as Nina Simone, made the ‘fro famous by rejecting white beauty aesthetics and promoting love for the natural way in which Black hair grows. This movement was put into motion by the Black Panthers in the United States during the ‘60s and ‘70s, with Black men and women discarding methods used to subdue the organic properties of their hair.

Agnès Varda is best known as one of the founders of the French New Wave, and for her pioneering devotion to filming women’s stories, but with Black Panthers, the filmmaker shifts the lens to the Oakland demonstrations in the summer of 1968, while her partner, Jacques Demy, was directing Model Shop in Los Angeles. The protests fought against the imprisonment of activist and Black Panthers co-founder Huey P. Newton, for allegedly shooting police officer James Frey. Watching Varda’s film 50 years later, as streets all over the world ignite with anger, fury and rage over more injustices against Black people in the hands of the police, feels like a true testament to how far we have come.

Varda’s cinematic choices highlight the awareness of her own privilege as a white French woman. By deciding to use a removed, ethnographic English-language voiceover to explain events, the neutral narrative is welcome, and refreshingly clear, amidst our current climate of unreliable sources covering the Black Lives Matter movement. Poetically, the voice paints the symbol of the panther as a beautiful black animal that never attacks, but defends itself ferociously.

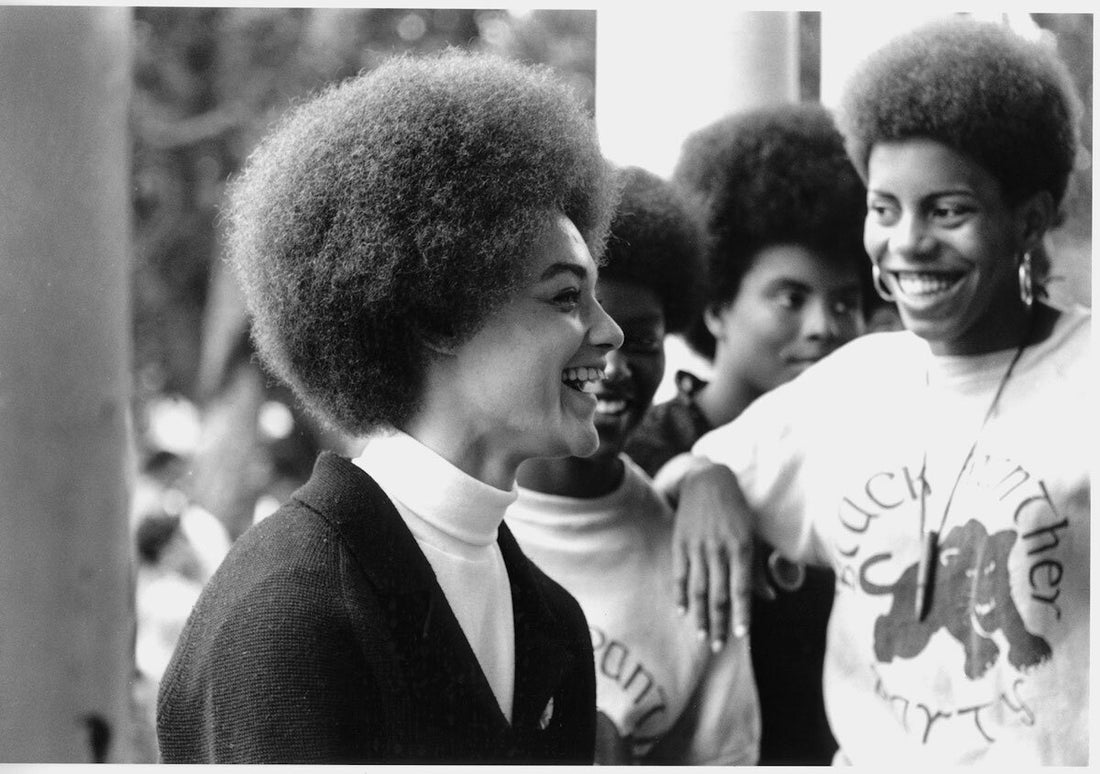

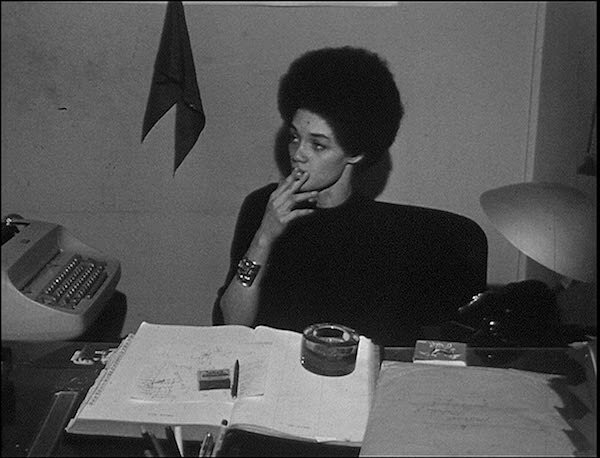

Kathleen Cleaver acts as Communications Secretary for the Black Panthers and is the first female member of the Party’s decision-making body. Varda catches Cleaver in a rare moment of intimacy, as she stresses the party’s approach to empowerment:

“For...many years we were told that only white people were beautiful – only straight hair, light eyes, light skin was beautiful...Black women would try everything they could – straighten their hair, lighten their skin – to look as much like white women. But this has changed, because Black people are aware now that their own appearance is beautiful, they’re proud of it.”

The party eliminated the need to use dangerous and demeaning methods to transform Black hair and Black skin, through promoting self-love and natural instruments used by our ancestors in Africa to nurture these features. In Kemet and West African cultures, the Afro comb was used as a status symbol, as decoration for the hair and as a tool carved out of wood and bone to maintain Black hair. Returning to African tradition and dress was a part of the Black Panthers ideology, with the symbol of the Afro pick coming to represent Black Power.

Newton delves into the ideology of the party in Black Panthers, speaking in an exclusive interview from prison. The Cuban revolution shaped their philosophy, the armed revolt influencing their militancy and affirming their championing of working-class people within a society that rewarded the rich. The party was one of the first organisations to struggle for ethnic minority and working-class rights, representing the need for all workers to take over the means of production through force and militance. Rejecting the capitalist economic system, the Panthers followed Malcolm X’s view of international working-class unity across the full spectrum of race and gender, implementing this by working with various minority groups and white revolutionary groups.

The current global pandemic has acted as a catalyst in initiating a worldwide cry for the end of institutional racism and demanding cultural gatekeepers to reassess their systems, to dismantle the oppressive cycles of oppression that originate at the top of society. Newton explains that since the time of slavery, Black men and women have been associated only with the body, and were seen to be inferior to the power of the mind, which was reserved for the white man – this echoes the feelings of many Black people today that governing bodies, educational institutions and systems in power do not support us fully. Black liberation in the 1960s and 1970s was about dissolving this divide between the mind and body and theorising our own revolution, for Black people to reclaim our own history.

The film ends on a bittersweet note, with the news that Newton has been convicted, exposing bullet holes left by police officers in an image of him in the window of the Black Panthers’ headquarters. The narration simply states: “The story of the Black Panthers is not over.”

The Black Power Mixtape 1967 – 1975 is an outsiders’ documentation of this period of resistance in American history by a group of Swedish filmmakers. On discovering the 16mm footage, which had been forgotten in a cellar beneath the Swedish National Broadcasting Company for three decades, filmmaker Göran Hugo Olsson felt a responsibility to bring this unguarded footage to light. Olsson worked with co-producer Danny Glover to weave these narratives together into a tapestry of images and music, resulting in a lively depiction of the evolution of the Black Power movement. The commentary from African-American artists and activists, including Erykah Badu, Talib Kweli and Questlove, injects the historical footage with strong contemporary voices and an understanding of how this movement continues to shape modern art forms. The Black British Artists movement in the UK, soul, jazz, Afrofuturism and the origins of hip hop are able to be traced back to this movement. Africa became a powerful symbol for a younger generation of Black American artists, a source of political identification, spirituality and musical inspiration. From the poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson to Nina Simone’s cries for freedom and Sun Ra’s mystical Jazz – music, poetry and literature were finely attuned to politics and during the 1960s and 1970s were adopted by the Panthers as a way to combat white oppression.

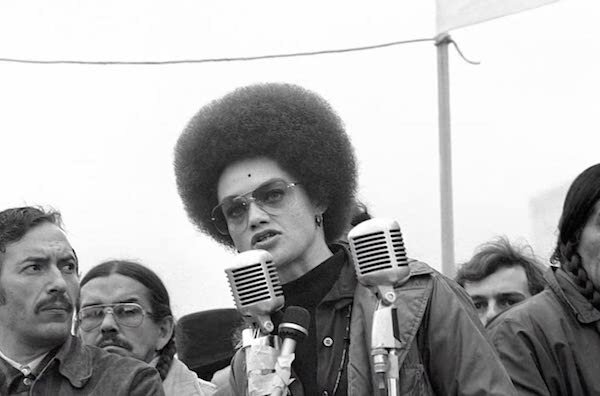

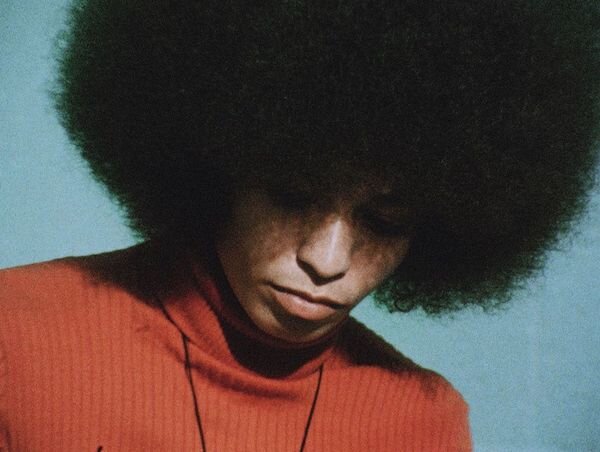

In 1971, activist and academic Angela Davis became America’s most famous political prisoner as she awaited trial, and Mixtape lays bare interview footage from 1972 when she was being detained in a small cell in San Francisco. Davis highlights the violence being exercised daily by those in power in America, and speaks on the overt racism of the police force towards Black people, and the ‘militant’ perception of the Afro. On the basis of her being a Black woman and having a ‘natural’ hairstyle the police assumed she might be a ‘militant’. Whilst living in Los Angeles she was constantly stopped and harassed on the basis of two sole things: being Black, and letting her hair exist as it grows.

In the article Afro Images: Politics, Fashion, and Nostalgia, Davis speaks on the humiliation of being remembered simply for her hairdo, reducing ‘a politics of liberation to a politics of fashion’ and demonstrating the fragility of historical images, particularly those associated with African American history. The Afro was not purely an aesthetic choice. What has been diluted is the opposition to capitalist structures such as the beauty industry inherent in Davis’s message, and ironically, the aesthetic of ‘blackness’ has been monetised as an agent of fashion in contemporary society. Hair offered a form of revolt, not just a fashion statement, but has been presented as such in our modern currency of transient images shared at the touch of a button. We must remember the theories and tenets that the Black Panthers preached – the visual only served to enforce and mirror the rhetoric that their philosophies were grounded in.

The Black Power Mixtape 1967 – 1975 begins at a juncture, when many young Black activists are growing tired of the nonviolent philosophy of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., opening with Stokely Carmichael promoting the concept of Black Power in the wake of Dr. King’s assassination. In a rare scene, Carmichael interviews his mother, Mable, on the effects of extreme poverty and discrimination and the effects of raising multiple children in such a harsh and hateful environment. A softer side to Carmichael is shown, and it becomes evident how his tough upbringing shaped his powerful speeches and disillusionment with Luther King’s philosophies of peace and forgiving the oppressor. The musings of present-day artists who have been influenced by this movement creates a concise relationship between past, present and future – the words deepening the understanding of what unfolds on screen and demanding the question: how did we get here?

The murder of George Floyd at the hands of white police officer Derek Chauvin prompted global protests demanding an end to the same cycles of systemic violence the Panthers fought for. Looking back to the Black Power movement is essential to acknowledge the work, struggle and inspiring legacies of community put into place – for instance, the Panther’s Free Breakfast for School Children Program, shown in The Black Power Mixtape 1967 – 1975, set up in January 1969 which, by the end of the year, had fed 10,000 children every day across America.

Both Black Panthers and The Black Power Mixtape 1967 – 1975 offer examples of the power of cinema in visualising the movement of Black Power in the 1960s and 1970s, and the unprecedented impact it had on Black hair and the ideals of beauty, freedom, and the way in which we protest today. Today, there is a dynamic range of stories on natural hair journeys and a huge well of healthy, nourishing products to choose from in an industry that now increasingly caters to the needs of Black hair. Our hair is going through a collective process of decolonisation, and personal experiences spanning the full spectrum of hair types are accessible within contemporary media. Finally, our voices are being amplified.

Maya Campbell (@mayajcampbell) is a South London based visual artist and writer who draws inspiration from femininity, nature and her dual cultural heritage. She is currently studying Photography at London College of Communication and running an online bookshop (@prajnabookshop) with her partner. Maya is presently researching the ancient practice of mask making, particularly the fetishisation within the African mask market