READ ME is a platform for female-led writing on film hosted by Girls on Tops. Louisa Maycock (@louisamaycock) is Commissioning Editor and Ella Kemp (@efekemp) is Contributing Editor.

How well do you really know Mother? Megan Christopher dives into 25 years of Tilda Swinton's unique relationship with gender to celebrate her new turn in Luca Guadagnino's Suspiria.

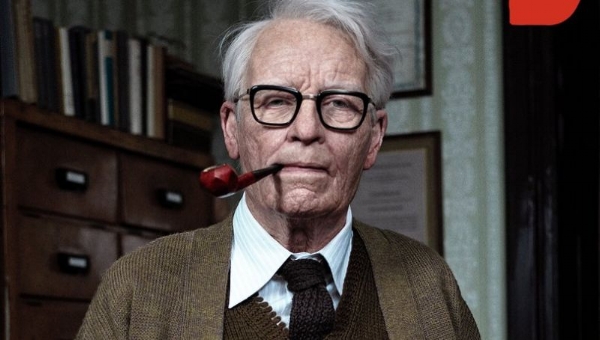

In 2017, during the production of Suspiria, Luca Guadagnino’s new homage to the 1977 Dario Argento film, news of a mysterious 82-year-old man dominated headlines: Lutz Ebersdorf, a supposed first-time German actor, would be taking on a major role in the movie. His IMDb page was blank save for an elaborate backstory, and no information could be found concerning any previous performances. The one thing that could be certain about Ebersdorf? He bore a strange resemblance to his co-star, Tilda Swinton.

Such a resemblance could have been overlooked as coincidental had this been any other actor, but Swinton’s body of work features characters so impenetrable that it all suddenly made sense. Of course, she had donned three hours worth of prosthetic makeup (courtesy of the award-winning makeup artist Mark Coulier) in order to play a man 25 years her senior. Of course. Swinton has a chameleonic approach to identity: from art installations and experimental films, to mainstream fantasy and queer cinema, her gender as an actor doesn’t seem to matter.

The dedication to the erosion of the gender binary is often looked upon as a modern concept, but one of the first definitions of postgenderism can be found in radical feminist Shulamith Firestone's 1970 book The Dialectic of Sex. In keeping with second-wave feminism, Firestone believed that gender should be abolished altogether in favour of a world where “genital differences between human beings would no longer matter culturally”. Despite mixed opinions from critics, the academic concept lived on: Guadagnino’s film now offers a new perspective through which to consider how the possibility of postgenderism applies to Tilda Swinton’s performative craft.

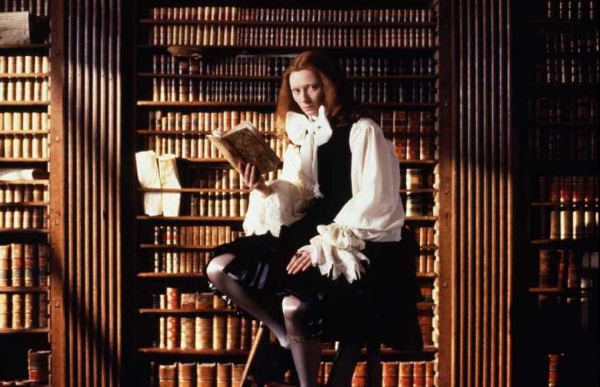

To understand how Swinton’s career has developed, we must rewind 25 years to the release of Sally Potter’s Orlando, a queer independent film that kickstarted the actor’s status as a non-gendered entity. The film follows an ageless, eponymous protagonist as he embarks on life as a wealthy nobleman before changing sex (and, arguably, gender) midway through the film. Played by Swinton throughout, Orlando is obsessed with the concepts of masculinity and femininity, as he/she responds to the heavily gendered world surrounding him/her.

The story rejects Orlando’s visual gender fluidity at first; “there can be no doubt about his sex,” speaks the voiceover, clearly defining him as male. Whilst Orlando may look feminine, the dialogue still reinforces a strict masculinity. Queen Elizabeth (Quentin Crisp) takes an instant shine to the young man, bestowing a fortune upon him and “his heirs”; an old-fashioned concept that bases strength in a male bloodline. Identity-based labels pepper the script, as Orlando is never a person or an individual, instead, always a “lord” or a “man”.

As the spoken words build these gendered walls, Potter’s flamboyant visuals immediately knock them down. Orlando frequently stares directly into the camera, a reminder of the female actress beneath the costume and a gauge on the fluidity of identity. An atmosphere of ridiculous excess reduces many minor characters to empty mockeries, as they exist purely to project gender onto a protagonist who cannot be defined. When Orlando’s body suddenly changes overnight, the viewer is reassured that they remain the same person, “just a different sex”. Potter reiterates gendered norms in the dialogue from those surrounding Orlando; when his/her sex comes under question, a doctor’s note declares her “unquestionably female”. The notion of a binary rooted in biology becomes increasingly absurd, as we realise that the only thing which has changed for the protagonist is the convention he/she is expected to uphold.

Orlando allows Swinton to embody a character that ultimately transcends gender. Since the film’s 1993 release, she has played androgynous angels (Constantine) and non-binary sorcerers (Doctor Strange), feminine blondes (The Limits of Control) and terrible mothers (We Need To Talk About Kevin). Female, male, neither or both – the actor encompasses all.

Suspiria introduces a new facet, as Swinton plays two major characters at once – an elderly male doctor and an enigmatic witch. Though she has played several characters in the same film before (in both Okja and Hail Caesar!), the gendered contrast between the two roles has never been greater. With her long hair and flowing clothing, Madame Blanc’s powerful elegance is fierce rather than traditionally genteel, but her character traits are nonetheless deeply rooted in femininity. This is further reinforced by her surroundings; as a teacher within a prestigious dance school, she is surrounded by women, and as a witch, she is inescapably linked to assumptions of feminine control. Her position in the coven hierarchy suggests her dominance within this female space. As a woman, she sets an example for the younger girls.

Dr. Josef Klemperer is based on an entirely different archetype – the figure of a wise old man. As a doctor, his dedication to science recalls more traditional associations of masculinity, and this forms a sharp contrast to the mystical, logic-defying witches. His appearance remains static and dull in comparison to Blanc: dressed in comfortable brown cardigans and knitted jumpers, Klemperer’s ‘maleness’ affords him the right to be practical about the clothes he wears. These differences are also reflected in the spaces he inhabits – Klemperer is an outsider to the feminine space of the school, only gaining access once he is relegated to the position of a sacrificial victim.

Swinton plays two heavily gendered characters in Suspiria, yet beneath the cosmetic differences the body remains the same. To the untrained eye, Klemperer may seem male and Blanc may seem female, and with the invention of Lutz Ebersdorf, Swinton’s presence was, for some time at least, concealed from public awareness altogether. In this situation, theoretical postgenderism would have been achieved through the lens of a camera, as the distinctions between Swinton and Klemperer blur – albeit with a bit of prosthetic help.

In the end the actor came clean about her dual roles, but the possibility of her keeping the secret begs the question: if one actress can play both binary genders within one film, without many even realising, is this a step towards a society that could exist past gender? Although societal norms reinforced over centuries might not be dismantled and destroyed by one actor, Swinton’s career provides a glimpse into a kaleidoscope of cinematic promise, where actors are not limited by their gender, nor their genitals. Mark Coulier, the film’s makeup artist, eventually revealed the weight the actor held in the commitment to her role. “She did have us make a penis and balls,” he said. “She had this nice, weighty set of genitalia so that she could feel it dangling between her legs, and she managed to get it out on set on a couple of occasions”.

As the restraints of gendered labels slowly dissolve in the film industry, it is certain that Swinton will continue to push the boundaries of the conventional in the people she plays. Postgenderism may still seem like a foreign idea to audiences around the world, but for Tilda Swinton, it’s just part of a normal day at the office.

Suspiria is now in cinemas, released by MUBI suspiria.com

Megan Christopher (@tinyfilmlesbian) is a freelance film journalist based in Manchester. Her particular filmic interest lies in portrayals of the LGBTQ+ community, mental health and women in general. She is a graduate in English Literature and American Studies, and the co-founder of Much Ado About Cinema.

Purchase our TILDA SWINTON t-shirt and help Girls on Tops continue to commission brilliant female-led film writing.